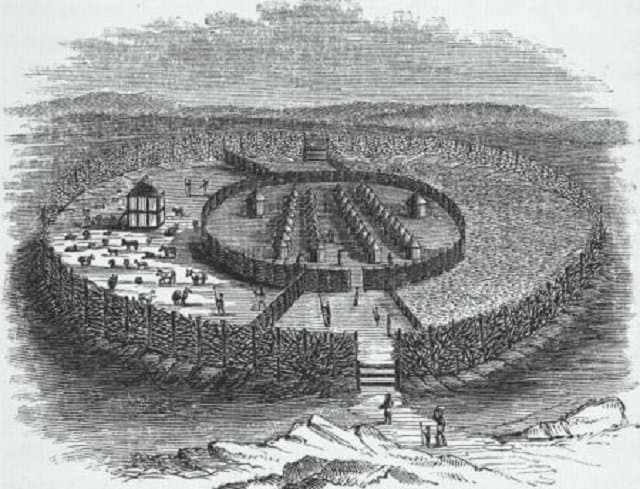

The Benin Kingdom, dating back to the 11th century, was one of the oldest and most advanced states in western Africa. Benin’s walls with their surroundings have been described as ‘the biggest earthworks in the world before the mechanical age,’ a man-made wondrous feature.

In 1897, during the Punitive Expedition, the Walls of Benin, one of Africa’s ancient architectural wonders, were burned.

This shocking act has destroyed the history of Benin for more than a thousand years and the earlier proof of rich African civilizations.

The incredible city was a collection of earthworks made up of banks and ditches in the area around present-day Benin City, named “Iya” in the Edo language. They are located in Iya city 15 kilometers away and the rural area around Benin is approximately 16 000 kilometres. For more than 400 years, the walls protected the people of the kingdom and the traditions and civilization of the people of Edo.

In the science magazine New Scientist, Fred Pearce wrote the following about the city: “In all, they are four times longer than China’s Great Wall and have absorbed a hundred times more content than the Great Cheops Pyramid. It took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to create and is possibly the planet’s largest single archaeological phenomenon.

The Guinness Book of Records (1974 edition) described Benin City’s walls and its surrounding kingdom as “the largest earthworks in the world carried out before the mechanical age.”

It was one of the first towns to be founded and put around the city with a semblance of street lighting with massive metal lamps, several feet high.

In 1691, captain of the Portuguese ship, Lourenco Pinto, observed: “Great Benin, where the king resides, is greater than Lisbon. The highways are all going straight for as far as the eye can see.

The houses are huge, especially the king’s, which is richly decorated and has beautiful columns. The town is rich and industrious. It is so well regulated that crime is unknown, and the people are living in such safety that they have no doors to their homes.

In his personal account, 17th-century Dutch visitor Olfert Dapper wrote, “Houses are built alongside the streets in good order, the one close to the other. Adorned with gables and steps … they are usually broad with long galleries inside, especially so in the case of the houses of the nobility, and divided into many rooms which are separated by walls made of red clay, very well erected.”

“[The walls are] as shiny and smooth by washing and rubbing as any wall in Holland can be made with chalk, and they are like mirrors. The upper storeys are made of the same sort of clay. Moreover, every house is provided with a well for the supply of fresh water,” he continued.

The Great Walls of Benin were about 16,000 km in length, 2nd only to the Great Wall of China (BR). Were world's largest man-made earth structure, and consumed 100 times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops. The City was destroyed by the British in 1897 #AfricanGlory pic.twitter.com/LMxFNrcc8y

— Charles Onyango-Obbo (@cobbo3) March 6, 2019

Benin City’s planning and design was done according to careful rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition now known as “fractal design”.

Ethnomathematician (the study of the relationship between mathematics and culture) Ron Eglash has discussed the planned layout of the city, commenting that “When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.”

“When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics they hadn’t even discovered yet.” – Ron Eglash

A lost city

The great city of Benin is lost to history after starting its decline in the 15th century. This decline was sparked by internal conflicts at the borders of the Benin Empire, linked to the increasing European intrusion and slavery trade. In the British Punitive Expedition in the 1890s, when the city was plundered, blown up and destroyed to the ground by British troops, it was then completely ruined.

In addition, the remaining ruins were neither maintained nor restored. The only remaining vestige is a house in Obasagbon that consists of a courtyard known as the house of Chief Enogie Aikoriogie. The house has features that fit the horizontally fluted walls, columns, central impluvium, and carved decorations seen in ancient Benin architecture. However, it is rumored that a part of the great city wall, one of the world’s largest man-made monuments ever, could lie abandoned in the Nigerian bush and be forgotten.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African