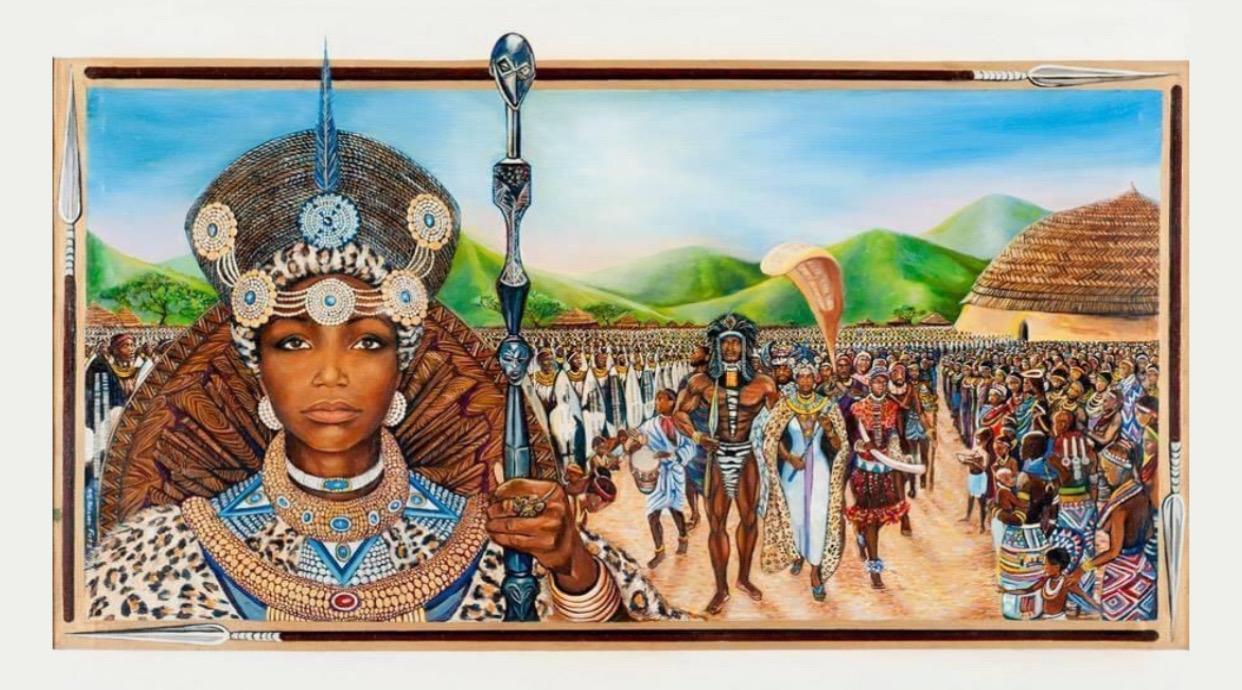

Queen Nandi ‘mother of Shaka Zulu’ buried with ten maidens alive to care for her

Nandi (c. 1760 – October 10, 1827) was a daughter of Bhebhe, a former chief of the Langeni nation and the mother of the famous Shaka, King of the Zulus. One of the greatest African military leaders.

In 1760, Queen Nandi Bhebhe was born in Melmoth. Her father was Bhebhe chief of Elangeni. The people of Elangeni (Mhlongo) had their king named Makhedama then.

Personal Life

Nandi Bhebhe was impregnated by Jama’s son, Senzangakhona, out of wedlock. For his non-traditional behavior, the Mhlongo people demanded Senzangakhona pay damages. To resolve the matter, the Mhlongo approached the Jamas. Nandi was at the forefront of this case and of the discussion. She personally requested 55 herds of cattle as payment for her damage, and the herd was given to the people of Mhlongo.

In order to prevent war, the Jamas and Senzangakhona accepted to pay the damages asked by the Mhlongo people. Senzangakhona, on the other hand, did truly love Nandi. Nandi initially spent considerable time at the Senzangakhona kraal after she gave birth to her son, Shaka, before her relationship with Senzangakhona worsened, forcing her to leave the kraal.

Nandi, returned to her people the Mhlongo of Elangeni, leaving behind Shaka. The life of Shaka in Senzangakhona’s kraal became difficult, and finally his uncle Mudli took him to Nandi at Elangeni. Nandi had to secure her son from hunger, assassination attempts and enemies during that period. Nandi’s stay at Elangeni, however, became unsafe as well, so she left to live among the Qwabe people with her son. She met Gendeyana there, whom she had married and had a son, Ngwadi.

It was not pleasant at all for Nandi to remain among the Qwabe people and this forced her to leave Qwabe to live among the Mthethwa people led by Chief Dingiswayo. The Mthethwa people welcomed Nandi generously. It was a good place for her to raise her sons, Shaka and Ngwadi, and Nomcoba, her daughter. Her son, Shaka, joined a Chwe regiment led by Bhuza. It was among the people of Mthethwa that Shaka developed military tactics.

Death of Queen Nandi

On October 10, 1827, Queen Nandi Bhebhe died of dysentery. Outside Eshowe, off the old Empangeni lane, her tomb can be found. The tomb is marked Nindi. On 11 March 2011 the Mhlongo Committee met at Eshowe with the Office of the KZN (kwaZulu-Natal) Premier and Amafa to finalise plans for Princess Nandi’s grave near Eshowe. It was concluded that Queen Nandi Bhebhe’s grave would be officially opened in May 2011 after the approval of the designs proposed by the Mhlongo people.

Queen Nandi Bhebhe was born into the Mhlongo people and for that reason it was also agreed that the name on the grave shall be “Princess Nandi Mhlongo, Mother of King Shaka”. The Bhebhe and Mhlongo people of eLangeni are one people. The immediate descendants of the mother of King Shaka, Nandi, were dissatisfied with the state of her grave, which for over 200 years had laid unattended in a bad state.

The Zulu Royal family blames the government for this because, according to them, the government is responsible for the graves of prominent figures. After the Mhlongo and the Royal family have resolved their differences, Amafa heritage, which administers protected structures in the province, will soon erect a sculptor symbolic of Nandi’s status.

Shaka loved his mother almost to the point of worship, despite the hard times they experienced together, or maybe because of them. For the love, Shaka buried her mother with ten maidens alive to care for her in the afterworld.

According to Donald Morris, during the following year of mourning, Shaka ordered that no crops to be cultivated, no milk (the basis of the Zulu diet at the time) was to be used, and any woman who became pregnant was to be killed along with her husband. At least 7,000 people were executed who were deemed to be insufficiently grief-stricken, although the killing was not specific to humans: cows were slaughtered so that their calves would know what it felt like to lose a mother.

What Morris states comes from the memory of Henry Francis Fynn. With some sources alleging that they were exaggerated because he may have had deeper motives, Fynn’s account was disputed. The earlier accounts of Fynn were sometimes inaccurate and exaggerated, which would become crucial to Zulu mythology’s growth. With the exception of a few who controlled the written record, many of the first white settlers were illiterate.

To obscure their own colonial agenda, these writers were accused of demonizing Shaka as a figure of inhuman qualities, a symbol of violence and terror. Julian Cobbing also argues that the writers of these settlers were eager to create a myth that “cover up” colonial slave raiding and general rapine across the sub-continent in the 19th century and justified the seizure of land.

Nandi story today is taught in some of the African schools making her one of the prominent females figures in African history.