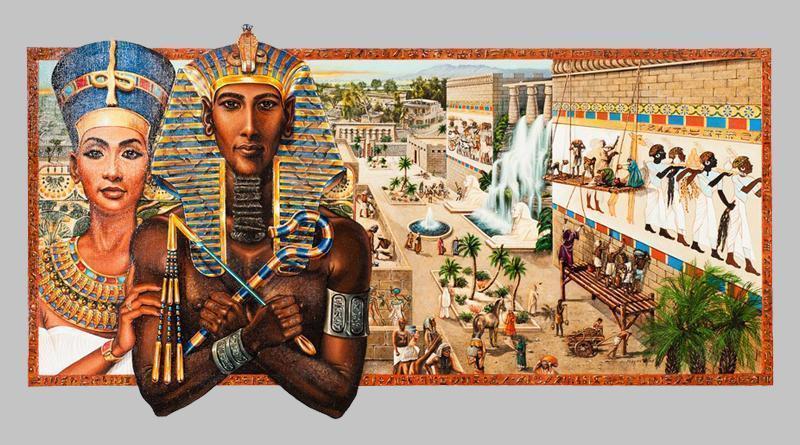

Amenhotep III and his wife Queen Tiye had a son called Akhenaten. Egypt ruled an empire that extended from Syria in west Asia to the River Nile fourth cataract in modern-day Sudan during their reign.

In 1887, about 350 tablets known as the “Amarna letters” were discovered near Akhenaten’s new capital, revealing diplomatic correspondence between Akhenaten, his fellow kings in west Asia, and vassals who owed the Egyptian king allegiance.

The letters show that during Akhenaten’s reign, an empire known as the Hittites, based in modern-day Turkey, became more assertive, going to war against the Mitanni, an Egyptian ally. In their book “Akhenaten and Tutankhamun: Revolt and Restoration,” Egyptologists David Silverman, Josef Wegner, and Jennifer House Wegner write, “In addition to their conflicts with the Mitanni, the Hittites were also stirring up disorder in the vassal states of Syria, and a nomadic group, the Apiru, was causing unrest in Syro-Palestine” (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2006).

They point out that previous Egyptian kings would have most likely launched a military expedition into west Asia in response to these acts, but Akhenaten seems to have done nothing. “Some modern scholars criticize Akhenaten for concentrating all of his attention on his religious ideas, causing Egypt’s international reputation to deteriorate as a result.”

Turning to the Aten

While Aten, the sun-disc, was nothing new in Egyptian religion, Akhenaten’s decision to put it at the center of religious life, to the point where the names of Amun and Mut were desecrated, was just something completely new.

Montserrat notes that at Karnak, a temple complex near Luxor, which was dedicated to Amun-Ra, the king would have built a series of Aten temples, whose construction might begin in his very first year of rule.

Even at this early stage, he seemed to have a dim view of the god Amun, whom Karnak had dedicated to. Montserrat notes that the axis of the new Aten complex was built to the east, towards the rising sun, while the rest of Karnak was to the west, where ancient Egyptians believed the underworld to be. “The first major building project of Akhenaten turns its back on the temple of Amun, perhaps anticipating events later in his reign,” wrote Montserrat.

Egyptologist James Allen notes in his book “Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphics” (Cambridge University Press, 2010) that sometime between the ninth and eleventh years of Akhenaten’s reign, he changed the long form of the name of the god so that, essentially, Aten became “not only the supreme god but the only god.”

This coincided with the beginning of a campaign aimed at disgracing the names of the gods Amun and Mut, among other deities. “Akhenaten’s minions began to erase the names of Amun and his consort, Mut, and to change the plural… ‘gods’ into the singular ‘god.’ To judge from later inscriptions, the temples of the old gods may also have been closed and their priesthoods abolished,” Allen writes.

This extraordinary event occurred throughout the empire of Egypt. “Care has been taken to erase the name of Amun from the letters in the diplomatic archive, the memorial scarabs, and the tips of the obelisks and pyramids; the distant regions of Nubia have also been affected, as far as Gebel Barkal in the Fourth Nile Cataract,” writes Egyptologist Erik Hornung in his book “Akhenaten and the Religion of Light” (Cornell University Press, 1999).

“In some instances, Akhenaten even had his own original personal name [Amenhotep, the name when he first assumed power] mutilated in his attempt to harm the hated Amun.

Still, Akhenaten seems to have been able to fully convince all Egyptians to place their only spiritual hope in Aten. Archaeologist Barry Kemp, who is leading modern-day excavations at the site of Amarna, notes in his book “The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti” (Thames and Hudson, 2012) that researchers have found figures depicting other deities, such as Bes and Thoth, in Amarna.

He also notes that few Egyptians seem to have added the word “Aten” to their name in honor of the god. In fact, the sculptor Thutmose, who created the iconic bust of Nefertiti that is now in the museum in Berlin, left his name in such a way as to honor the god Thoth.

Grotesque art

In addition to his radical religious changes, Akhenaten has also launched a revolution in the way art has been drawn. Before his time, Egyptian art, especially those depicting royalty, tended to show a rigid, structured, formal style.

This changed radically in Akhenaten’s time, with people drawn with cone-shaped heads and thin, spindly limbs. The royal family was even drawn in such a way as to convey intimate moments. One depiction, reproduced in Hornung’s book, shows Akhenaten and Nefertiti riding a horse-drawn carriage, both of whom appear to be kissing each other with the rays of Aten shining on them.

This radical departure from art, in particular the distorted shape of the body, has long left Egyptologists mystified. Hornung writes that, in 1931, the German Egyptologist Heinrich Schäfer said, “Anyone who stands in front of some of these representations for the first time withdraws from this epitome of physical repulsion. His [Akhenaten’s] head seems to float over his long, thin neck. His chest is sunk, yet there is something feminine about its shape. Below his bloated paunch and his fat thighs, his skinny calves match his spindly arms…” Schäfer observed.

Why Akhenaten has chosen to portray himself and others in this way is a mystery. It was assumed that he had suffered from a severe physical deformity that had made him change the Egyptian style of art. However, the recent study of a mummy in KV 55, in the Valley of the Kings, which some believe is Akhenaten, shows no evidence of serious physical deformities.

Kemp writes in his book that if it is true that Akhenaten was not deformed, then we must look into the psyche of a man to find the answers to this mystery. “The images are a wake-up call that someone is not in the mainstream of humanity. He’s one of a kind, on the edge of it. He wants you to feel uncomfortable and yet – as conveyed through relaxed poses and overt affection for his family (as found in some of the arts) to love him at the same time.”

The dark side of Amarna

Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.

In addition, Tutankhamun would condemn the actions of Akhenaten in a stela found in Karnak. Part of it reads, “The temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the marshes of the Delta… had fallen into decay, and their shrines had fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass… The gods ignored this land…”

[From the City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Barry Kemp]The message was clear, that through his radical religious changes, Akhenaten had turned his back on the gods and so offended them. Tutankhamun and his successors would restore the way they had been before. Whether or not Akhenaten wanted people to love him, recent research shows that the people who built his new city, out in the desert, paid a steep price.

Recent research published in the journal Antiquity shows that the common people in Amarna have suffered from nutritional deficiencies and a high rate of juvenile mortality, even by the standards of the time.

Children had stunted growth, and many bones were porous due to nutritional deficiency, probably because the commoners lived on a diet of mostly bread and beer, Archaeologist Anna Stevens told LiveScience in an interview at the time the research was published.

Researchers also found that more than three-quarters of adults had degenerative joint disease, likely from heavy loads, and about two-thirds of these adults had at least one broken bone, as reported in the LiveScience story.

Death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten are shrouded in mystery. Until recently, Egyptologists have noted that Nefertiti’s name appears to have vanished around the year 12 of his reign, when the last of his major monuments was built.

It has been speculated that she may have fallen out of favor with Akhenaten, or that her name has been changed to become the co-ruler of Egypt. The recent discovery, however, challenges all of this. In December last year, Egyptologists with the Dayr-al-Barsha project announced that they had found an inscription dated to year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign (shortly before his death), which mentions Nefertiti and shows that she was still Akhenaten’s “chief wife” (in the researchers words).

Whatever happened in Akhenaten’s final years, his religious changes and his new capital would not have survived his death. Within a few years of his death (which occurred around 1335 B.C.) a new king named Tutankhamun, now believed by many researchers to have been Akhenaten’s son, ascended the throne.

A boy king, he was originally named Tutankhaten, in honor of Aten, but his name was changed to honor Amun, the god that his father had tried to wipe out. During Tut’s reign, Egypt would return to its original religious beliefs, and Amun and Mut would assume their place at the top of the Egyptian pantheon of gods.

The capital that Akhenaten had built would have been abandoned within a few decades of his death, and the “heretic king” would have been dishonored, not even included in some of Egypt’s king lists.