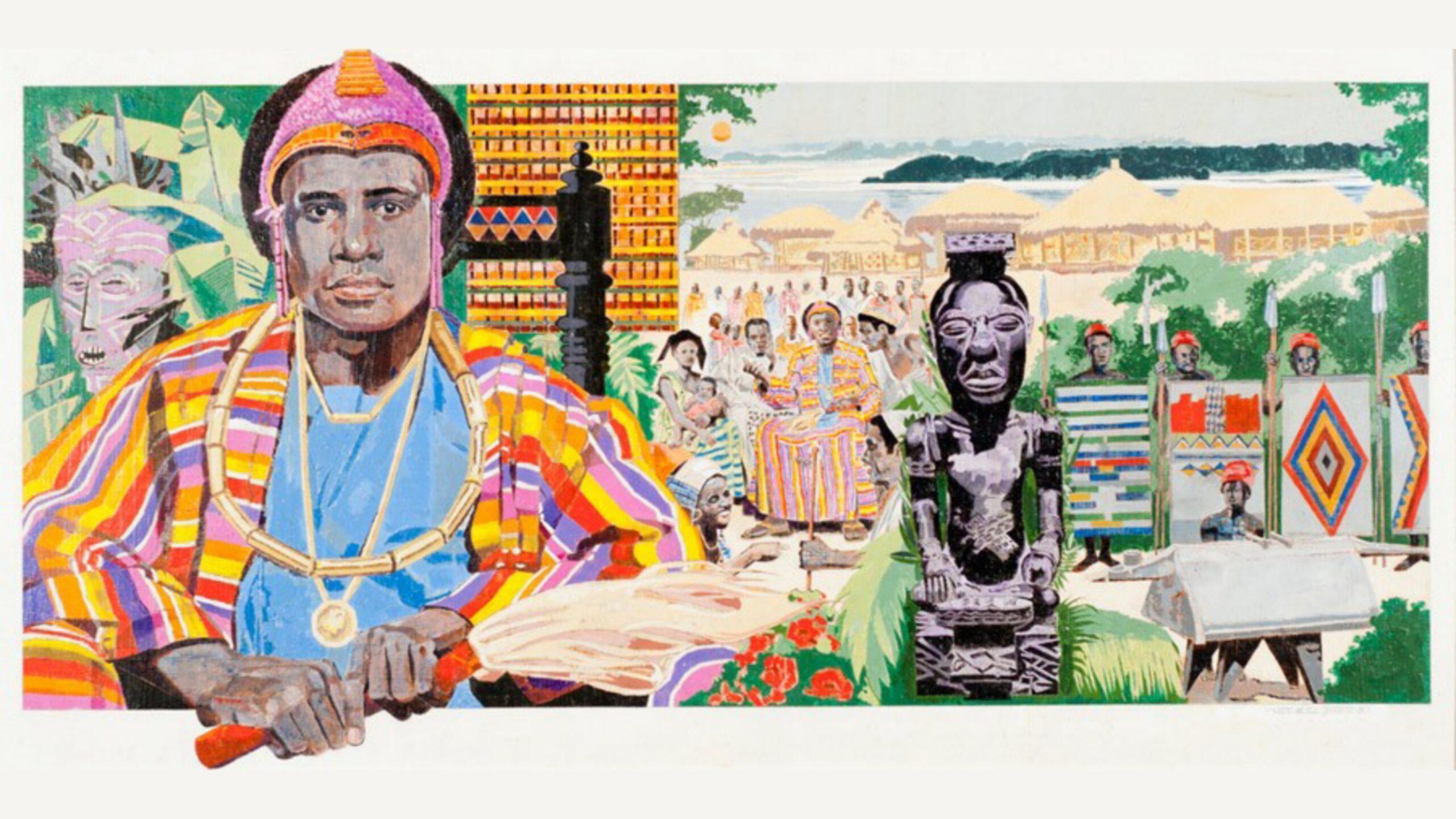

Shamba Bolongongo (c. 1600), the 93rd king, who introduced weaving and textile manufacture to his people, he was also the first Kuba ruler to have his portrait carved in wood. Shamba Bolongongo’s portrait established a tradition of such portraiture among the Kuba people.

Kuba cultural area

The Kuba art is one of the most advanced of all African cultures, and they have a long history of important cultural achievements. Mucu Mushanga, their 27th king, is credited with inventing fire and being the first to wear bark cloth clothing. Shamba Bolongongo (c. 1600), the 93rd king, was the first Kuba ruler to have his portrait carved in wood. He introduced weaving and textile manufacturing to his people.

The portrait of Shamba Bolongongo formed a tradition of portraiture among the Kuba people. The kings generally sit with their legs crossed in front of them, the left in front of the right; the right hand sits on the right knee with fingers extended, and the left hand holds the royal dagger.

The stomach is covered in geometric patterns, which continue on the back of the figure. Objects important to each king are also included in the sculptures, showing his personal achievements.

A common style that emerged from the court style was geometric forms rather than the well-modeled full-volumed forms of the court figures. Kuba fetishes are strongly schematic, highlighting only important organs. The popular style can be seen in the Kuba’s utensils and textiles as well.

The Kuba metalsmith worked with copper, iron, and brass to produce weapons and tools that were both beautiful and useful. One metal was inlaid with another in some instances. Mashamboy and other masks, which were usually made of raffia and embellished with shells, beads, and even bells and feathers, were used to dramatize the establishment of the royal dynasty and its matrilineal descent method.

Luba cultural area

Although the Luba people (Kinshasa, southeastern Congo) have an aggressive and warlike past, their artistic style is distinguished by the harmonious combination of organically related forms.

Carvings of female figures are more common than carvings of male figures. Others are kneeling, sitting, or standing figures whose upraised hands serve as supports for bowls, seats, and neck rests. Some are freestanding, almost always in a frontal position with their hands on their breasts; others are kneeling, sitting, or standing figures whose upraised hands serve as supports for bowls, seats, and neck rests.

A kneeling or sitting female figure holding a bowl is a common form. Such mendicant figures are used to pray to spirits for health and assistance for pregnant women; when neighbors see the figure in front of a woman’s hut, they would fill it with gifts to help her escape pregnancy hardship. The female figures are modeled in rounded forms and have a stylistic tendency toward plumpness known as dodu.

Buli’s “long-face style” is one of the most well-known Luba substyles. Its roundness contrasts sharply with that of other Luba figures. The faces are elongated and graceful, with angular features.

The Songe, who both conquered and were conquered by the Luba, developed a sculptural style with a lot of movement and vitality. Their fetishes, made from wood or horn and embellished with shells and polychrome, are not as realistic as typical Luba fetishes, but their use of nonnaturalistic, more geometric forms is impressive.

The Songe often make ceremonial axes out of iron and copper with interlaced designs on them. Kifwebe masks, which combine human and animal features painted in red, black, and white, are common among one community.

The Chokwe and Lunda invaded the Luba kingdom in the 19th century; today, these hunters and farmers live in a region that includes parts of northern Angola and southern Congo. Their individual styles are often indistinguishable.

Both male and female figures are carved in an impressively vigorous manner, and the shapes they develop are monumental and weighty. Chairs with figures posed in genre and iconic scenes are often created by these individuals. All items, including utensils like combs and knives, have zoomorphic motifs. Men wear painted bark cloth masks and net costumes during initiation rites.

Northern cultural area

The Lega, who live between the Luba and the northernmost tribes, have produced figures and masks, most of which are carved in a schematic style from ivory. These objects, along with a large assemblage of artifacts and natural objects, are used in the Bwami association’s initiation to successive grades.

Northeast cultural area

The Mangbetu and the Zande remain in the northeast. The elongated skull forms created by binding the heads of young children are popular in Mangbetu sculpture, which is done in wood, ivory, and pottery. The sculpture of Zande appears to be largely Mangbetu in nature.

The cultural area of the Northwest

The Ngbaka and Ngbandi are two peoples whose sculptures are especially significant in the northwest. There is no single Ngbaka sculptural style: the figures can be fleshy and rounded at times, or they can be angular at other times. In hunting, small animal figures are used as fetishes. The circumcision masks are made in a clever way.

Clay images are made by both the Ngbaka and the Ngbandi for use in funeral rituals. Wooden fetishes and figures are also common among the Ngbandi. Ngbandi warriors wore small carved ivory or wood figures and shields made of painted woven fiber. It’s always difficult to tell the difference between the few Ngbandi masks and the Ngbaka masks.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African