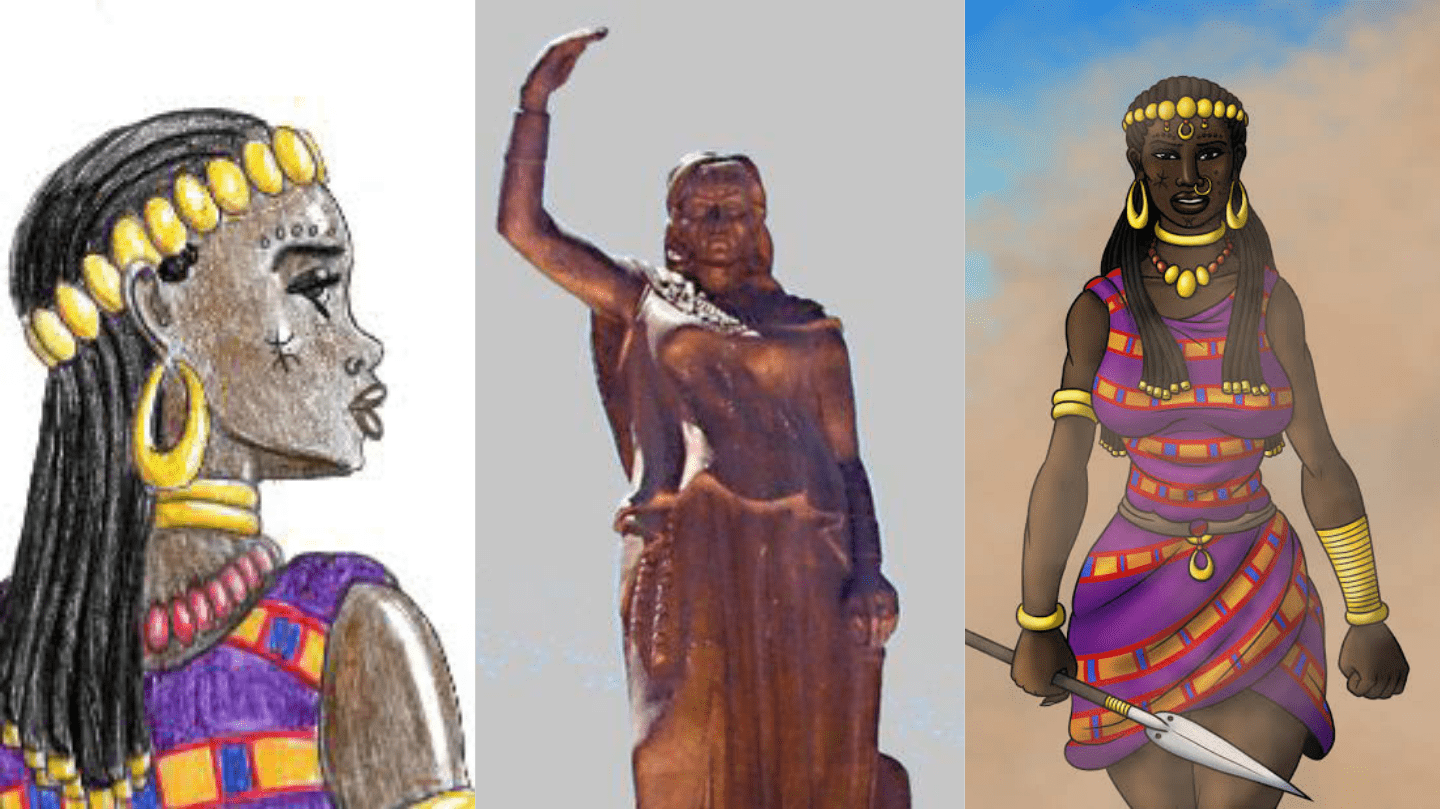

Dihya, also known as Al-Kahina, was a Berber queen and religious and military leader who led indigenous resistance to the Muslim invasion of the Maghreb, also known as Numidia at the time. She was born in the early seventh century and died nearly end of the seventh century in present-day Algeria.

Origins and Religion

Her given name either of one of the following variations: Daya, Dehiya, Dihya, Dahya, or Damya.

Arabic-language sources referred to her as al-Khina. Her Muslim critics called her this because of her reported ability to predict the future.

Dihya was born into the Jrwa Zenata tribe in the early seventh century.

She ruled a free Berber state from the Aurès Mountains to the oasis of Gadames for five years (695–700 CE). However, the Arabs, led by Musa bin Nusayr, returned with a huge army and overcame her. She fought at the El Djem Roman amphitheater before being killed in battle near a well that bears her name, Bir al Kahina in Aures.

According to accounts dating back to the nineteenth century, she was of Jewish faith or belonged to a Judaized Berber tribe. She was followed in her journeys by a “idol,” according to al-Mlik. Both Mohamed Talbi and Gabriel Camps saw this idol as a Christian symbol, either of Christ, the Virgin, or a saint guarding the queen. According to M’hamed Hassine Fantar, this symbol depicted a separate Berber idol, making Dihya a pagan. However, Dihya’s Christian status remains the most likely theory.

The medieval historian Ibn Khaldun, who identified the Jarawa as one of seven Berber tribes, is credited with the fact that they were Judaized. Hirschberg and Talbi observe that Ibn Khaldun appears to be referring to a period before the arrival of the late Roman and Byzantine empires, and that a little later in the same paragraph seems to suggest that “the tribes” had been Christianized by Roman times.

In 1963, the Israeli historian H.Z. Hirschberg questioned this interpretation, as well as the existence of large Jewish Berber tribes at the end of Antiquity, by retranslating Ibn Khaldun’s text and rigorously repeating the entire document. According to H.Z. Hirschberg, “Among all known movements of conversion to Judaism and incidents of Judaizing in Africa, those associated with the Berbers and Sudanese are the least authenticated. Whatever is written on them is highly dubious.”

Al-Mlik, a Tunisian hagiographer, appears to have been among the first to say she lived in the Aurès Mountains four centuries after her death. The pilgrim at-Tijani was told she belonged to the Lwta tribe just seven centuries after her death. When Ibn Khaldun, a later historian, came to write his account, he assigned her to the Jarawa tribe.

Al-Khinat was the daughter of Tabat, or Mtiya, according to various Muslim sources.

These sources depend on tribal genealogies, which were traditionally made up for political purposes in the 9th century.

Many legends about Dihy are documented by Ibn Khaldun. Several of them make reference to her long hair or large stature, both of which are legendary attributes of sorcerers. She is often said to have had the gift of prophecy and to have had three sons, which is typical of witches in legends.

Even the fact that two of her children were her own and one was adopted (an Arab officer she had captured) was an alleged characteristic of sorcerers in folklore. Another legend has it that when she was younger, she allegedly freed her people from a tyrant by deciding to marry him and then killing him on their wedding night. Nothing more about her personal life is known.

Conflicts and legends

In the 680s, Dihya succeeded Kusaila as war leader of the Berber tribes, opposing the encroaching Arab Islamic forces of the Umayyad Dynasty. Hasan ibn al-Nu’man marched from Egypt and invaded Carthage and other major Byzantine cities (see Muslim conquest of North Africa).

Looking for another opponent to beat, he was informed that the most dominant ruler in North Africa was “the Queen of the Berbers,” Dihy, and marched into Numidia as a result. At the Battle of Meskiana (or “battle of camels”) in Algeria in 698, the armies met near Meskiana[10], in the present-day province of Oum el-Bouaghi.

She defeated Hasan so thoroughly that he left Ifriqiya and spent four or five years hiding out in Cyrenaica (Libya). Recognizing that the enemy was too strong and would return, she is said to have launched a scorched earth campaign, which had little effect on the mountain and desert tribes but cost her the great assistance of the sedentary oasis dwellers. Instead of stopping Arab armies, her desperate intervention fueled their defeat.

The Kahina story is told by various cultures, and each story always provides a different, or even conflicting, viewpoint. The novel, for example, is used to support feminist values. Furthermore, Arabs use it to spread their own nationalism.

For the Arabs, they told the tale in such a way that the Kahina seemed to be a sorcerer, all in an effort to undermine her. Some Arab historians went even further, claiming that the Kahina finally sought to convert her sons to Islam. The French were another community who told the tale of the Kahina. The Kahina tale was told to paint colonialism in a positive light. The tale was told with the message that it reflected the liberation of Berbers from Arab rule.

Another, lesser-known account of Dihy claimed that she was interested in early desert bird studies. Although this viewpoint may or may not be credible, some evidence has been recovered at her death site in modern-day Algeria. Several fragments of early parchment with a bird painting on them were discovered, but there’s no way to know if the fragments belonged to her. However, since the painting depicted a Libyan bird species, it is likely that she developed her interest while in Libya.

Defeat and death

Hasan later returned and, supported by connections with Dihya’s captured officer “Khalid bin Yazid al-Qaysi,” defeated her at the Battle of Tabarka (a location in modern-day Tunisia near the Algerian border).

According to some sources, Dihya died battling the invaders with the sword in hand. According to other sources, she committed suicide by swallowing poison rather than being captured by the enemy. This final act happened in the 690s or 700s CE, with 703 CE being the most probable year. According to Ibn Khaldun, she was 127 years old that year. This is clearly one of the many controversies that surround her.

According to many historians, Bagay and Khenchla converted and led the Berber army to Iberia. However, according to historian Ibn al-Athr, they died with their mother.

Legacy

The Kahina’s identity is uncertain. As a result, she has been appropriated by a variety of parties. She can be Berber, Oriental, Byzantine, Jewish, Christian, or pagan. Just one thing is certain: she was a woman. Women adopted her as a symbol, and she was used as a symbol of resistance to foreign occupation, and later as a symbol of resistance to male hegemony.

Indeed, during the time of French colonisation, the Kahina served as a model for revolutionary women fighting the French. During the Kabyle insurgency of 1851 and 1857, women regarded as chief warriors, such as Lalla Fatma N’Soumer and Lalla Khadija Bent Belkacem, looked to the Kahina for inspiration.

In addition, in the early twentieth century, the French, eager to Frenchify Algeria by Romanizing its history, draw comparisons between themselves and the Romans. Algerian nationalists, trying to link Algeria to the East, draw the same comparisons, but both Rome and France are imperial forces, responsible for the collapse of Phoenician civilization in the past and Arabic civilization in the present. Kahina’s mythology served as a foundational myth for both philosophies. On one hand, she fought the Arabs and Islam to keep Algeria Christian, while on the other, she fought all invaders (Byzantines or Arabs) to establish an independent state.

In the present day, Berber activists often use the image of the Kahina to demonstrate how they, as a community, are powerful and will not be conquered or weakened by other cultures. Her face is often depicted in graffiti and sculptures throughout Algeria to demonstrate people’s support for the political values she represents.

Although her true appearance is uncertain, artists have represented her in ways that support the political cause she is considered to embody. However, not all governments support the Kahina’s principles. The government condemned a statue of the Kahina in Baghai for blasphemy. According to the president of the Arab Language Defense Association, the Kahina embodied Islam’s opposition and therefore should be condemned.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African