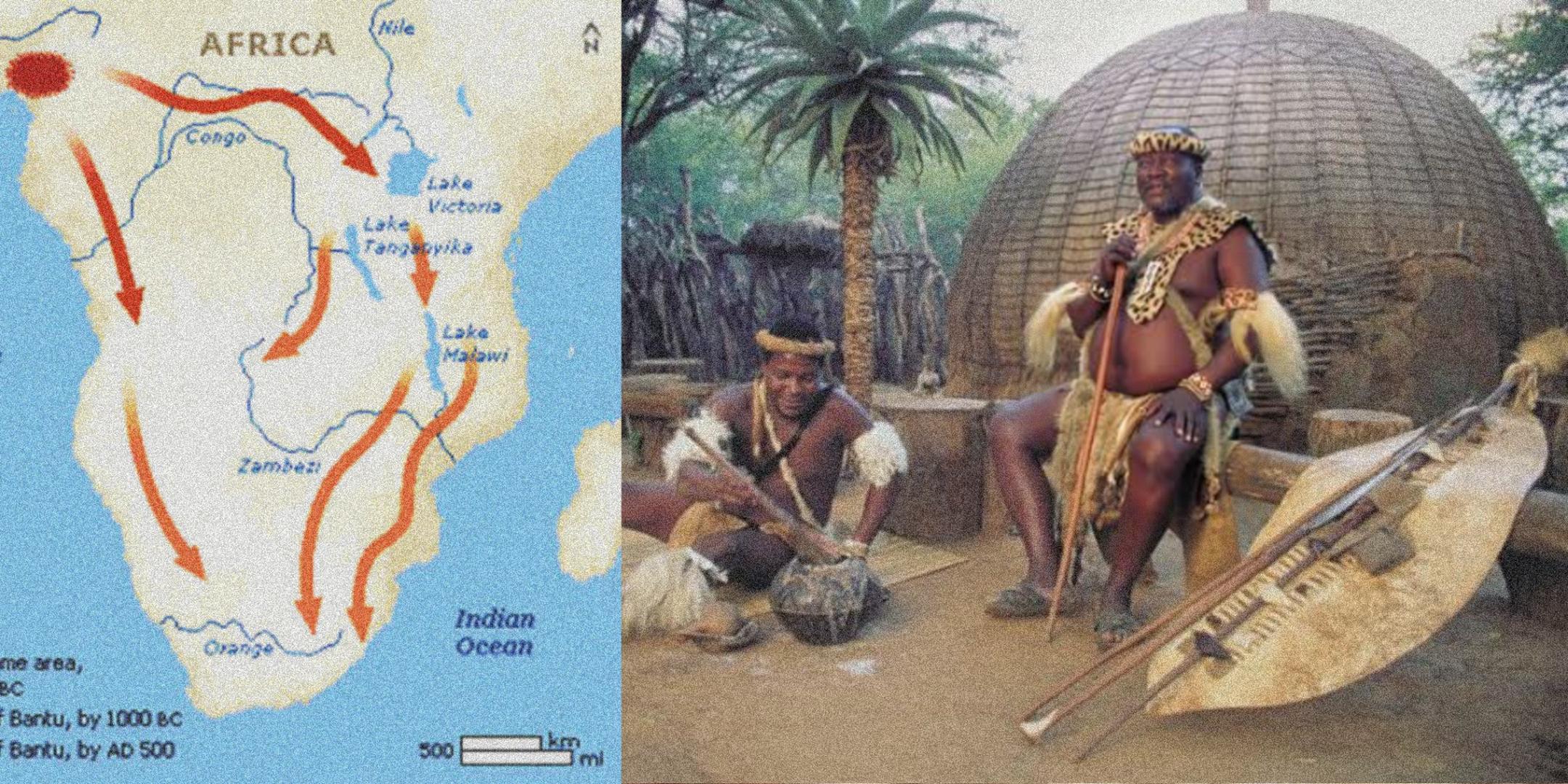

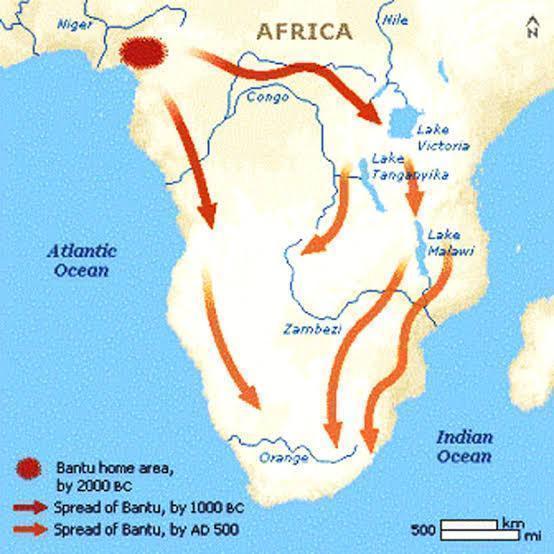

Bantu-speaking Africans, for whom the descendants make up the vast majority of South Africa’s current population, had moved south of the Limpopo River around 1,500 years ago.

The Bantu speakers came from West Central Africa, north of the Congo River, near present-day Cameroon, and combined knowledge of cattle-keeping and slash-and-burn (swidden) cultivation with metal-working expertise.

Historians and archaeologists now believe that this movement occurred not as a single large migration, but rather as a slow southward shift of people across Sub-Saharan Africa caused by the gradual drying up of the Sahara, which began around 8,000 years ago.

The southward movement involved a moving frontier of farmers seeking new fields and pastures who interacted with pastoralists and hunter-gatherers, sometimes trading, sometimes incorporating people into client relationships, and sometimes fighting for access to the same critical resources.

Farmers settled throughout southern Africa east of the 400-millimeter rainfall line and as far as the Great Kei River’s southwestern limits of cropping.

In their use of the environment, Bantu-speaking farmers chose to minimize risks rather than maximize output. They kept large herds of cattle and bestowed great material and symbolic value on these animals.

Cattle were used for significant social and political transactions, such as bridewealth compensation (lobola ) and tribute demands, and they provided a means to acquire and display significant wealth.

Cattle were also valued for their milk and hides, but except on ceremonial occasions, they were rarely slaughtered for their meat. Game hunting remained a major source of protein, with domesticated goats and sheep providing additional supplies.

Bantu speakers also grew a variety of indigenous crops such as millet, sorghum, beans, and melons, as well as other grains and vegetables. Those who lived near the sea caught shellfish and fished.

By utilizing such a great range of food sources, the farmers spread their risks in a difficult ecological system constantly subject to drought, disease, and crop failure.

Nonetheless, the accumulation of large herds and the cultivation of extensive fields resulted in higher population concentrations and significantly more stratification among Bantu speakers than among their San and Khoikhoi neighbors.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence of settlements with tens of thousands of people that were established more than 1,400 years ago. Toutswe, in eastern Botswana, was a collection of communities built on large flat-topped hills with fields below and cattle pastured locally.

Residents smelted iron and traded extensively with people from as far east as the Indian Ocean. Similar large communities arose at least 1,000 years ago, just south of the Limpopo River, where Bambandyanalo and then Mapungubwe emerged as important early states (both situated at the intersection of the present-day borders of Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa).

Residents of these states cultivated vast fields and raised large herds of cattle while also producing finely worked gold and copper ornaments, hunting for ivory, and engaging in extensive long-distance trade. They were generally presided over by chiefs who wielded considerable—but never absolute—power; elders were always consulted on major decisions.

In comparison to the smaller-scale communities of San and Khoikhoi, Bantu-speaking societies exhibited greater levels of stratification: old over young, men over women, rich over poor, and chiefs over commoners.

However, there were significant differences in the settlement patterns and degree of political centralization established by Bantu speakers who settled inland and those who settled closer to the coast.

The inland Bantu speakers, known as Sotho-Tswana because of their dialects, grouped in greater numbers near water sources and trading towns. By the late sixteenth century, a succession of powerful hereditary chiefs ruled over the Rolong society, whose capital was Taung.

The capital and several other towns, which served as agricultural and livestock hubs as well as major trading hubs, had populations ranging from 15,000 to 20,000 people. In contrast, the Bantu-speaking Nguni, who settled on the coastal plains between the Highveld and the Indian Ocean, lived in much smaller communities and had less hierarchical political structures.

They lived in small communities scattered across the countryside, moving their cattle frequently in search of new pastureland. In many cases, a community identified itself based on descent from some ancestor, as the Zulus and Xhosa did. Such communities, like the Xhosa, Mpondo, Mthethwa, and others, could sometimes grow to a few thousand people, but they were usually much smaller.

By 1600, Khoisan peoples in the west and southwest, Sotho-Tswana in the Highveld, and Nguni along the coastal plains had settled all of what is now South Africa.

Shipwrecked Portuguese travelers and sailors in the seventeenth century reported seeing large concentrations of people living in apparent prosperity.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African