Ruby Bridges born in 1954 was the first African American child to integrate an all-white public elementary school in the South. She later became a civil rights activist.

Who Is Ruby Bridges?

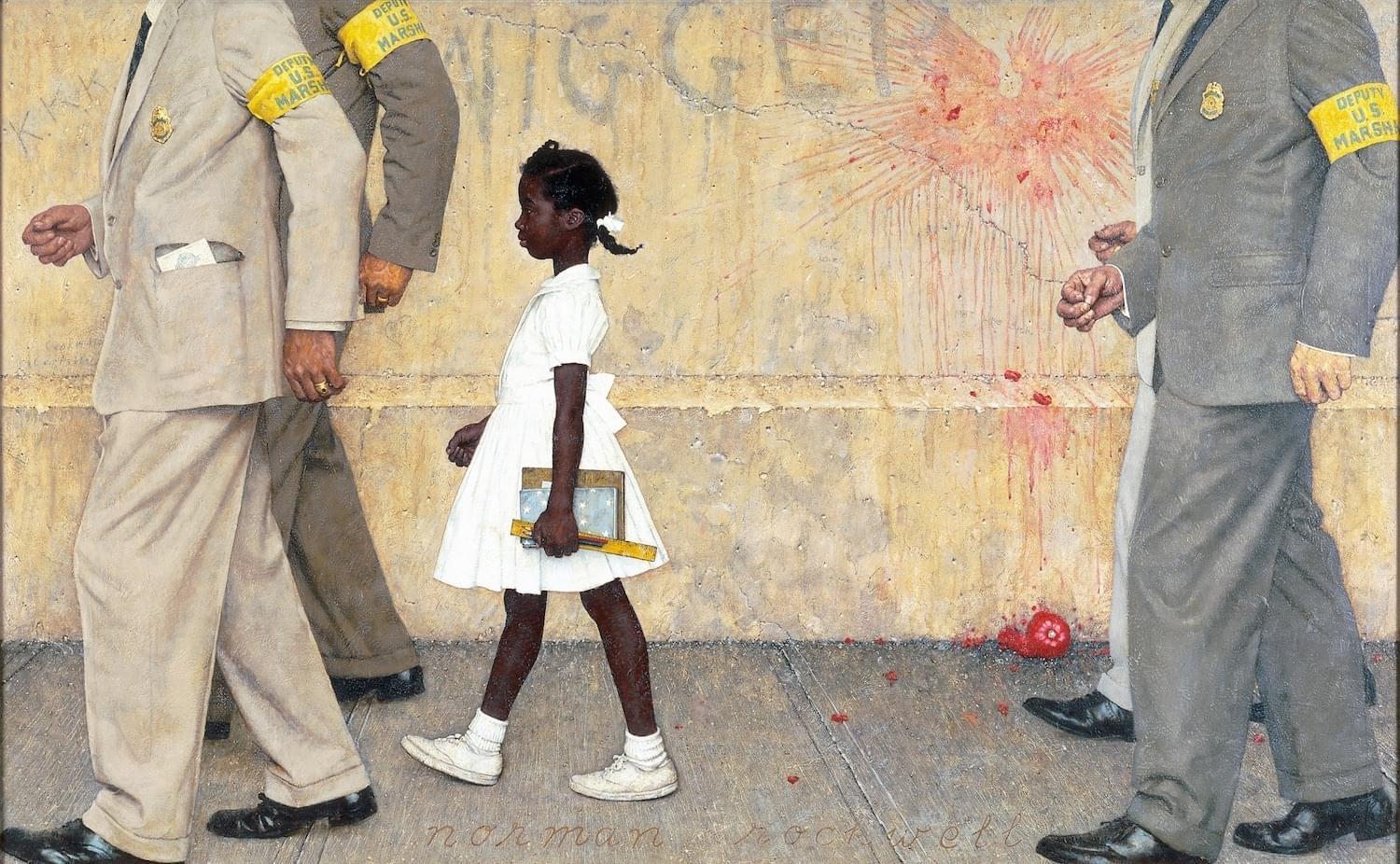

When Ruby Bridges was six years old, she became the first African American child to attend a predominantly white Southern elementary school. Due to angry mobs, her mother and U.S. marshals accompanied her to class on November 14, 1960. Bridges’ heroic act was a watershed moment in the civil rights movement, and she used educational platforms to share her story with future generations.

Early Life

Ruby Nell Bridges was born in Tylertown, Mississippi, on September 8, 1954. She grew up on a Mississippi farm that her parents and grandparents shared.

Her parents, Abon and Lucille Bridges, relocated to New Orleans when she was four years old, looking for a better life in a bigger metropolis.

To support their increasing family, her father accepted a job as a gas station attendant, and her mother took night jobs. Bridges was soon joined by two younger brothers and a younger sister.

Education and Facts

Bridges was born in the same year that the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling desegregated schools, which was a significant coincidence in her early civil rights work.

Bridges was one of several African American youngsters in New Orleans who were picked to take a test to determine whether or not she could attend a white school when she was in kindergarten.

According to reports, the test was intended to be particularly difficult so that pupils would struggle to pass. The idea was that if all of the African American children failed the test, the schools in New Orleans would be able to remain segregated for a little longer.

Bridges lived just five blocks from an all-white school, but she went to an all-Black segregated kindergarten many miles away. Bridges’ father was opposed to her taking the test, believing that if she passed and was permitted to attend the white school, violence would ensue.

Bridges’ mother, Lucille, insisted on attending a white school, believing that she would receive a higher education. She eventually convinced Bridges’ father to allow her to take the test.

Officials from the NAACP informed Bridges’ parents in 1960 that she was one of only six African American pupils who had passed the test. Bridges would be the first Black child to attend an all-white primary school in the South and the only African American student at the William Frantz School, which is close to her home.

School Desegregation

Bridges was still at her former school when the first day of school arrived in September. The Louisiana State Legislature had sought ways to fight the federal court decision and slow the integration process during the summer and early fall. The Legislature had to concede after exhausted all stalling tactics, and the targeted schools were to be integrated in November of that year.

Fearing civil unrest, a federal district court judge in New Orleans requested that federal marshals be dispatched to the city to protect the youngsters. Federal marshals took Bridges and her mother five blocks to her new school on November 14, 1960. One of the men explained to Bridges in the car that when they got at the school, two marshals would walk in front of her and two would walk behind her.

Large crowds of people were gathered in front of the school when Bridges and the federal marshals arrived, screaming and throwing things. Barricades had been erected, and police officers were stationed across the area.

Bridges mistook it for a Mardi Gras event when she was younger. She was brought to the principal’s office and spent the entire day there after entering the school under the protection of federal marshals. Classes were canceled that day due to the chaos outside and the fact that nearly all of the white parents at the school had kept their children at home.

Ostracized at Elementary School

Bridges’ second day began in much the same way as the first, and it appeared for a time that she would be unable to attend class. Bridges was only taught by one teacher, Barbara Henry. She was a new teacher at the school, hailing from Boston. Bridges, who referred to her as “Mrs. Henry” even as an adult, embraced her with open arms.

Because parents had pulled or threatened to pull their children from Bridges’ class and send them to other schools, Bridges was the sole student in Henry’s class. Henry and Bridges sat side by side at two desks for a year, concentrating on Bridges’ lessons. Bridges was surrounded by Henry’s love and care, and he assisted her not only with her studies but also with the unpleasant experience of being rejected.

The first several weeks at Frantz School were difficult for Bridges. She was often challenged with overt racism in the presence of her federal escorts. A woman threatened to poison her on her second day of school. Following that, the federal marshals only permitted her to eat food from her home. She was “greeted” by a woman holding a Black doll in a wooden coffin on another occasion.

Bridges’ mother encouraged her to stay strong and pray when she entered the school, which she realized decreased the vehemence of the insults and gave her strength. Mrs. Henry’s classroom was her home for the whole day, and she was not allowed to go to the cafeteria or out to playground to interact with other pupils. The federal marshals escorted her down the corridor when she needed to use the restroom.

Bridges shown a lot of courage, according to federal marshal Charles Burks, one of her escorts, several years later. “She just marched along like a tiny soldier,” Burks recalled, adding that she never wept or groaned.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African