Harriet Tubman (c. 1820–1913) escaped slavery to become a leading abolitionist. She led hundreds of enslaved people to freedom along the route of the Underground Railroad.

Who Was Harriet Tubman?

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery in Maryland and escaped to freedom in the North in 1849, becoming the Underground Railroad’s most renowned “conductor.” On this sophisticated hidden network of safe homes, Tubman risked her life to lead hundreds of family members and other slaves from the plantation system to freedom. Tubman, a famous abolitionist before the American Civil War, also aided the Union Army throughout the conflict, serving as a spy among other things.

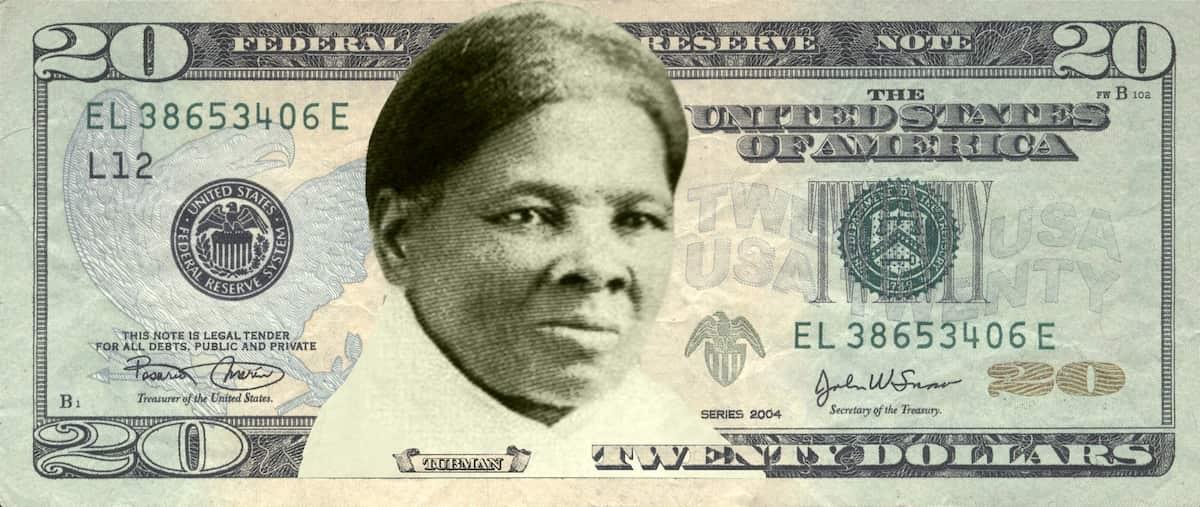

Tubman dedicated her life after the Civil War to assisting destitute former slaves and the elderly. In 2016, the United States Treasury Department announced that Tubman will replace Andrew Jackson on the center of a new $20 bill in commemoration of her life and public demand.

Early Life and Family

Tubman’s birth year is unclear, however it was most likely between 1820 and 1825. She was one of nine children born to enslaved parents in Dorchester County, Maryland, between 1808 and 1832. Mary Pattison Brodess owned her mother, Harriet “Rit” Green. Anthony Thompson owned her father, Ben Ross (Thompson and Brodess eventually married).

Tubman was born Araminta Harriet Ross and was given the nickname “Minty” by her parents. Around the time of her marriage, Araminta changed her name to Harriet, probably to honor her mother.

Tubman’s early years were filled with adversity. Three of Tubman’s sisters were sold to distant farms by Mary Brodess’ son Edward, severing the family. Rit successfully resisted the further disintegration of her family when a dealer from Georgia approached Brodess about buying Rit’s youngest son, Moses, setting a powerful example for her young daughter.

Tubman and her family had to deal with physical assault on a regular basis. Her bodily injuries were permanent as a result of the assault she experienced as a child. Tubman later recalled being slashed five times before breakfast on one particular day. She would have to live with the scars for the rest of her life.

Tubman’s most serious injury came while she was a teenager. She was sent to a dry goods store for supplies and came across a slave who had escaped the fields without authorization. Tubman’s overseer ordered that she assist in restraining the fugitive. When Tubman refused, the overseer whacked her in the head with a two-pound weight. For the rest of her life, Tubman suffered from seizures, terrible headaches, and narcoleptic episodes. She also had religious experiences, which she defined as vivid dream states.

For Tubman and her family, the boundary between freedom and slavery was unclear. Tubman’s father, Ben, was set free from slavery at the age of 45, according to a previous owner’s will. Despite this, Ben had few options but to continue working for his former employers as a wood estimator and supervisor.

Despite the fact that Rit and her children were subject to similar manumission conditions, the family’s owners chose not to release them. Despite his status as a free man, Ben had little power to overturn their judgment.

Husbands and Children

Harriet Tubman, a free Black man, married her in 1844. Around half of the African Americans on Maryland’s eastern shore were free at the time, and it was not uncommon for a household to include both free and enslaved members.

There is little information on John or his marriage to Harriet, including whether or whether they lived together and for how long. Because the mother’s position influenced the status of any offspring, any children they produced would have been considered enslaved. John chose to stay in Maryland with his new wife rather than travel on the Underground Railroad with Harriet.

Tubman married Nelson Davis, a Civil War veteran, in 1869. Gertie, a baby girl, was adopted by the couple in 1874.

The Underground Railroad and Siblings

Tubman traveled from the South to the North on the Underground Railroad network 19 times between 1850 and 1860. She led more than 300 individuals from slavery to freedom, including her parents and several siblings, receiving the moniker “Moses” for her efforts.

Tubman first encountered the Underground Railroad in 1849, when she attempted to flee slavery. Tubman decided to flee slavery in Maryland for Philadelphia after a bout of illness and the death of her master. She feared for the future of her family, as well as for her own fate as a frail slave with little economic worth.

On September 17, 1849, she was accompanied by two of her brothers, Ben and Harry. After seeing a notice in the Cambridge Democrat offering a $300 reward for Araminta’s return, Harry and Ben changed their minds and returned to the plantation. Tubman had no intention of remaining in captivity. After seeing her brothers safe and sound, she went out on her own for Pennsylvania.

Tubman walked over 90 miles to Philadelphia through the Underground Railroad. “When I found out I had crossed that border, I glanced at my hands to see if I was the same person,” she said later, recalling her relief and wonder as she passed into the free state of Pennsylvania. Everything was bathed in brilliance; the sun shone like gold through the trees and across the plains, and I felt as if I were in Heaven.”

Rather than staying in the safety of the North, Tubman made it her duty to use the Underground Railroad to free her family and others who were enslaved. Tubman received word in December 1850 that her niece Kessiah, together with her two young children, would be sold. At an auction in Baltimore, Kessiah’s husband, a free Black man called John Bowley, placed the winning offer for his wife. The entire family was then assisted by Tubman in making the trek to Philadelphia. Tubman’s journey was the first of many.

As a result of the law, Tubman rerouted the Underground Railroad to Canada, which outright abolished slavery. Tubman led a group of 11 fugitives north in December 1851. According to evidence, the party came to a halt at the home of abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass.

Tubman met abolitionist John Brown in April 1858, who urged the use of violence to disrupt and eliminate the institution of slavery. Brown’s ideals were shared by Tubman, and he at least tolerated his methods. Before they met, Tubman claimed to have had a prophetic vision of Brown.

Brown appealed to “General Tubman” for assistance when he began collecting followers for an attack on slaveholders at Harper’s Ferry. Tubman lauded Brown as a martyr after Brown’s killing.

During the Civil War, Tubman stayed active. Tubman began his career as a cook and nurse for the Union Army before becoming an armed scout and spy. She led the Combahee River Raid, which emancipated over 700 slaves in South Carolina, and was the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war.

Later Life

Senator William H. Seward, an abolitionist, sold Tubman a tiny plot of land on the outskirts of Auburn, New York, in early 1859. Tubman’s family and associates found refuge on the farm in Auburn. Tubman stayed on this land for years after the war, looking after her family and others who had moved there.

Despite her renown and notoriety, Tubman never had a stable financial situation. Tubman’s supporters and friends were able to raise some money to help her. Sarah H. Bradford, one of Tubman’s admirers, authored a book called Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, with the earnings benefiting Tubman and her family.

Despite her financial difficulties, Tubman continued to donate generously. She gave a piece of her property to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Auburn in 1903. In 1908, the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged was built on this site.

How Did Harriet Tubman Die?

Tubman died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913, at the age of 93, surrounded by friends and family. Tubman’s head injuries, which she acquired early in her life, became increasingly severe and disruptive as she grew older. She had brain surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to relieve the symptoms and “buzzing” she was experiencing on a regular basis. Tubman was eventually admitted to the nursing home that was named for her. She was laid to rest with military honors in Auburn’s Fort Hill Cemetery.

Legacy

Tubman was well-known and revered when she was alive, and in the years following her death, she became an American icon. According to a poll taken at the turn of the century, she was the third most renowned person in American history before the Civil War, behind Betsy Ross and Paul Revere. She has inspired generations of Americans who have fought for civil rights.

Tubman’s life was honored by the city of Auburn with a plaque on the courthouse when she died. In the twentieth century, Tubman was honored in a variety of ways around the country. Several schools have been named after her, and the Harriet Tubman Home in Auburn and the Harriet Tubman Museum in Cambridge are both memorials to her life.

Tubman’s life and work were commemorated in the 1978 film A Woman Called Moses, and her service as a conductor for the Underground Railroad was portrayed in the 2019 film Harriet.

Tubman on the New $20 Bill

The United States Treasury Department announced in April 2016 that Tubman would replace Jackson as the face of a new $20 bill. Following Women on 20s’ campaign to have a prominent American woman appear on U.S. currency, the Treasury Department received a flood of public comments, prompting the announcement. Tubman devoted her life to racial equality and battled for women’s rights, therefore the decision was hailed.

Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew was chastised in June 2015 for claiming that a woman would almost certainly appear on the $10 bill, which has a likeness of Alexander Hamilton, the prominent founding father who has regained prominence thanks to the Broadway musical Hamilton. Tubman’s replacement of Jackson, a slaveholder who assisted in the expulsion of Native Americans from their land, was greatly praised.

The new $20 bill featuring Tubman was set to be unveiled in 2020, on the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. However, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin declared in May 2019 that no new designs would be released until at least 2026, citing counterfeiting concerns. The inspector general of the Treasury Department announced in June that he would investigate why the launch had been delayed.

The Biden administration stated in January 2021 that it is “exploring ways to speed up” the release of the Tubman $20.

Movie

Tubman’s life was recounted in the 2019 film Harriet, starring Cynthia Erivo as Tubman, from her first marriage to her service freeing the enslaved. For her performance, Erivo was nominated for an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, and a Screen Actors Guild Award.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African