According to recent research, climate change was a major factor in the demise of large creatures across Africa over the last several million years, contradicting the long-held view that our first weapon-wielding ancestors had a role.

Archaeologists and paleontologists have yet to figure out when and why megafauna, such as enormous elephants and antlered giraffes, went extinct.

The arrival of early human predecessors, who drove them to extinction, was widely assumed to have had an impact on Africa’s rich biodiversity in the ancient past.

However, the current study casts doubt on the theory, claiming that there have been few attempts to test it or consider alternate theories.

Long-term environmental change, according to scientists at the University of Utah, caused the extinctions, mostly through deforestation and grassland expansion due to lowering atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels.

The findings show that large herbivore species began a long-term decline around 4.6 million years ago, long before our ancestors with tools became a threat to the animals.

Our forefathers split from 4 to 7.5 million years ago, but tools, the utilization of animal carcasses, and hunting came much later. Although the earliest stone tools were used 2.4 million years ago, considerable levels of hunting did not begin until 50,000 years ago, according to the fossil record.

The study was directed by Tyler Faith, curator of archaeology at the Natural History Museum of Utah and assistant professor in the University of Utah’s Department of Anthropology.

“Our studies suggest that since roughly 4.6 million years ago, there has been a sustained, long-term drop in megaherbivore variety,” he added.

“This extinction process begins over a million years before the first evidence of human predecessors creating tools or butchering animal carcasses, and much before any hominin species capable of hunting them, such as Homo erectus.”

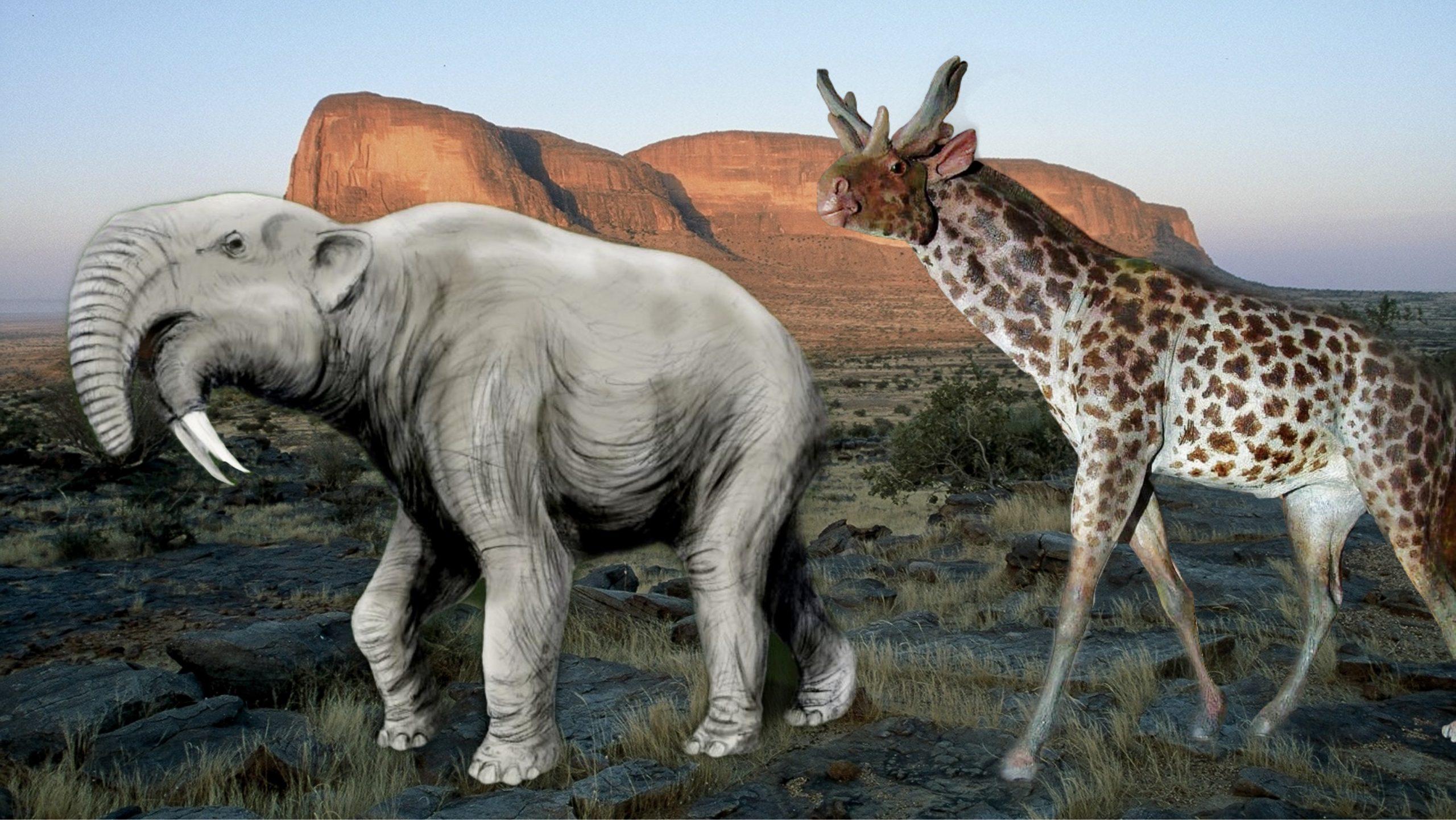

Many large creatures no longer walk the world, including Deinotherium – a mighty elephant with backwards-curving tusks that weighed twice as much as an African bush elephant – would have been witnessed by our evolutionary forefathers in Africa.

Two huge baboon species existed, the largest of which was around the same size as a current gorilla.

The Sivatherium, a relative of the contemporary giraffe and possibly the world’s largest ruminant, was one of the oddest creatures. The species was built like a giraffe, standing over 3m tall and weighing more than a tonne, but with a stag’s head and two pairs of antlers.

Professor Faith and his team looked at data from over 100 fossil records over the last seven million years to figure out why these and other megaherbivores died out.

They also looked at climate and environmental records, notably global atmospheric CO2 trends, stable carbon isotope records of vegetation structure, and stable carbon isotopes of eastern African fossil herbivore teeth, as well as their consequences.

According to their findings, significant megaherbivore extinctions happened over the last seven million years, with 28 lineages becoming extinct, leaving today’s societies devoid of huge creatures.

“The spread of grasslands, which is likely tied to a global drop in atmospheric CO2 over the previous five million years, appears to be the primary factor in the Plio-Pleistocene megaherbivore collapse,” said co-author John Rowan, a postdoctoral scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“Because low CO2 levels favor tropical grasses over trees, savannas have become less woody and more open through time.” We know that many extinct megaherbivores ate woody plants, therefore they appear to vanish along with their food source.”

Other extinctions attributed to archaic hominins could be explained by the demise of these huge herbivores.

Previous research has revealed that over the last few million years, competition with increasingly carnivorous animals of early human ancestors contributed to the extinction of countless predators. However, a new study suggests another option.

“We know there are also major extinctions among African carnivores at this time,” said co-author Paul Koch of the University of California. “Some of them, like sabretooth cats, may have specialized on very large prey, perhaps juvenile elephants.” “It’s possible that some of these carnivores and their megaherbivore prey vanished together.”

“Looking at all of the probable drivers of megaherbivore decline, our findings imply that changing temperature and environment had a crucial role in Africa’s historical extinctions,” Professor Faith stated.

The study is published in the journal Science.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African