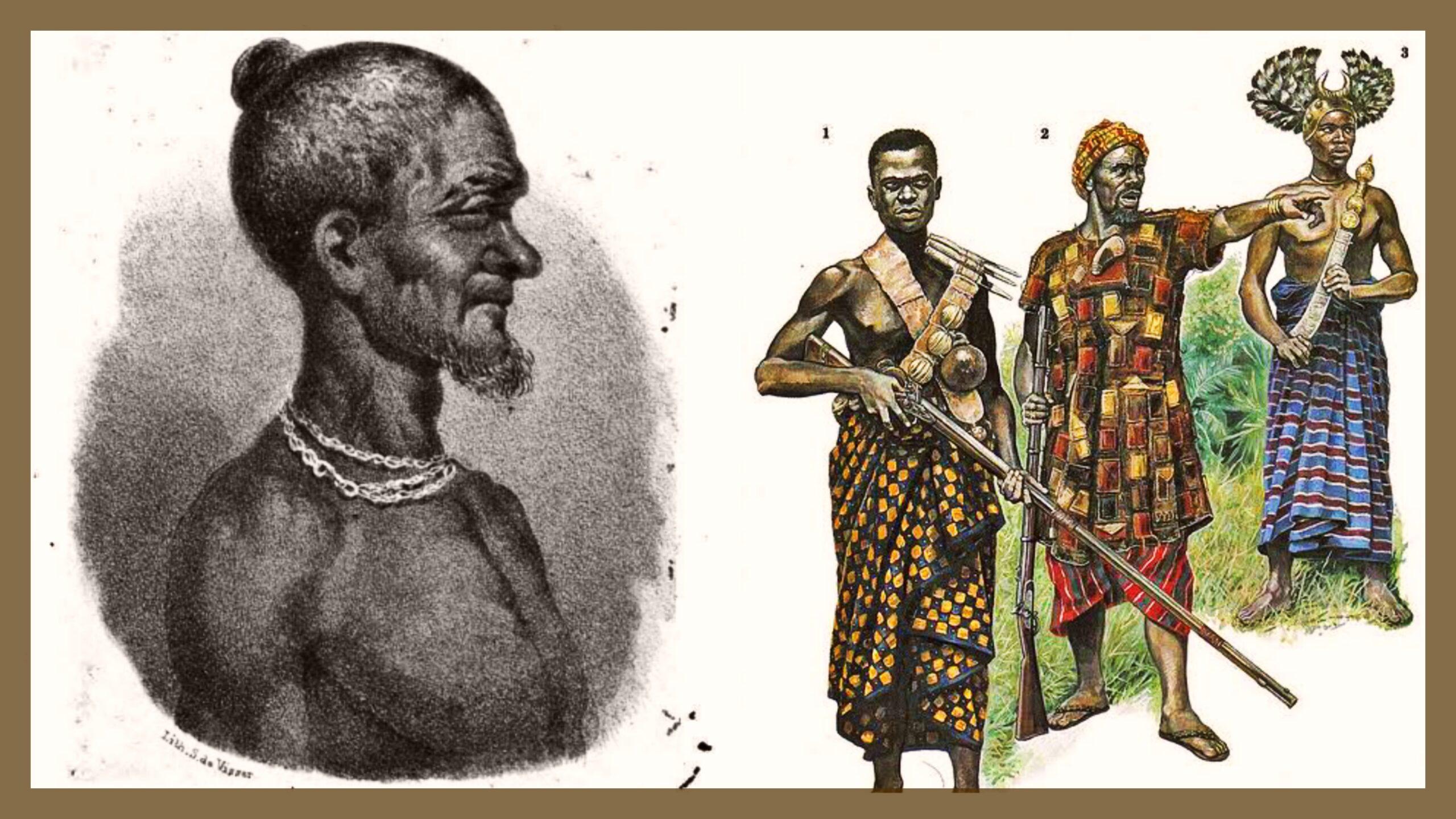

Badu Bonsu II was a Ghanaian king and chief of the Ahanta who was innocently executed in 1838 by the Dutch, who controlled the Dutch Gold Coast at the time.

Rebellion against the Dutch

We all know King Badu was ruling his people in his land without outsiders interrupting the peaceful living the Ghanaian people at that time.

King Badu was not pleased with the interference of the Dutch people grabbing land by force from the native and getting involved in the kingdom affairs.

In 1837, Badu Bonsu II mobolized his warriors and rebelled against the Dutch government, and killed several officers, including acting governor Hendrik Tonneboeijer.

The Dutch government justified military action against Badu Bonsu by citing the Treaty of Butre, and an expeditionary force was sent to Ahanta.

During the resulting battle, the king was arrested, tried for murder, and hanged. The Dutch dismantled the Ahanta regime, naming their commandant of Fort Batenstein at Butre as regent and holding the nation under tight control with an expanded military and civilian presence.

Following King Badu Bonsu’s execution, his body was desecrated when a Dutch surgeon removed his head. The head was transported to the Netherlands, where it was quickly lost for more than a century.

Rediscovery and return of the head

The head was rediscovered in the Netherlands in the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) by Dutch author Arthur Japin, who had read the account of the head while researching his 1997 novel De zwarte met het witte hart. Japin discovered the head in formaldehyde at the LUMC in 2005.

Government officials declared in March 2009 that it would be returning to its homeland for proper burial, a vow that was fulfilled on July 23, 2009, following a ceremony in The Hague.

Preserved in a jar of formaldehyde, the head of King Badu Bonsu II was discovered

gathering dust in a laboratory in the Leiden University Medical Centre by Arthur Japin, a best-selling Dutch author. It had been there since its arrival in the late 1830s from what was then called the Dutch Gold Coast and is today Ghana.

Mr Japin, the Dutch novelist, explained how he had helped reunite Badu Bonsu II head

with his body. “I was researching my novel about an Ahanta boy brought to Holland in

1838, and in the process I learned about the head of the king, who had been a friend of the boy,” he said.

“I had been looking for the head for more than 10 years because as a novelist you

become obsessed with finding out everything possible about your subjects. Finally, in

2002 I found it locked away in a dark cupboard where it had been for more than 170 years.

“The staff took it out of the round jar and put it on the laboratory sink for me. It had

been turned white by the formaldehyde but it was still life-size and he looked as if he was asleep. I felt, ‘this is so wrong, you should go home’.”

The Return

After hearing of the head’s location in 2008, Ghana filed a request for its return, saying, “Without burial of the head, the deceased will be hunted in the afterlife.”

In March 2009, government officials announced that it would be returned to its homeland for proper burial.

The Dutch and Ghanaian governments and a member of Badu Bonsu’s Ahanta tribe

signed a pact in The Hague for the handover of the head, which remained out of sight in a room elsewhere in the foreign ministry building for the ceremony.

Ahanta tribe leaders held an emotional ritual, pouring alcohol on the floor of the

conference room while invoking the chief’s spirit in the presence of Ghanaian nationals dressed in the country’s red and black mourning colours.

Ghana claimed the head of Badu Bonsu II, which had been preserved in formaldehyde in

a bottle among the anatomy collection of the university in the western Dutch town of

Leiden on July 23, 2009.

Credit: Ghana museum

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African