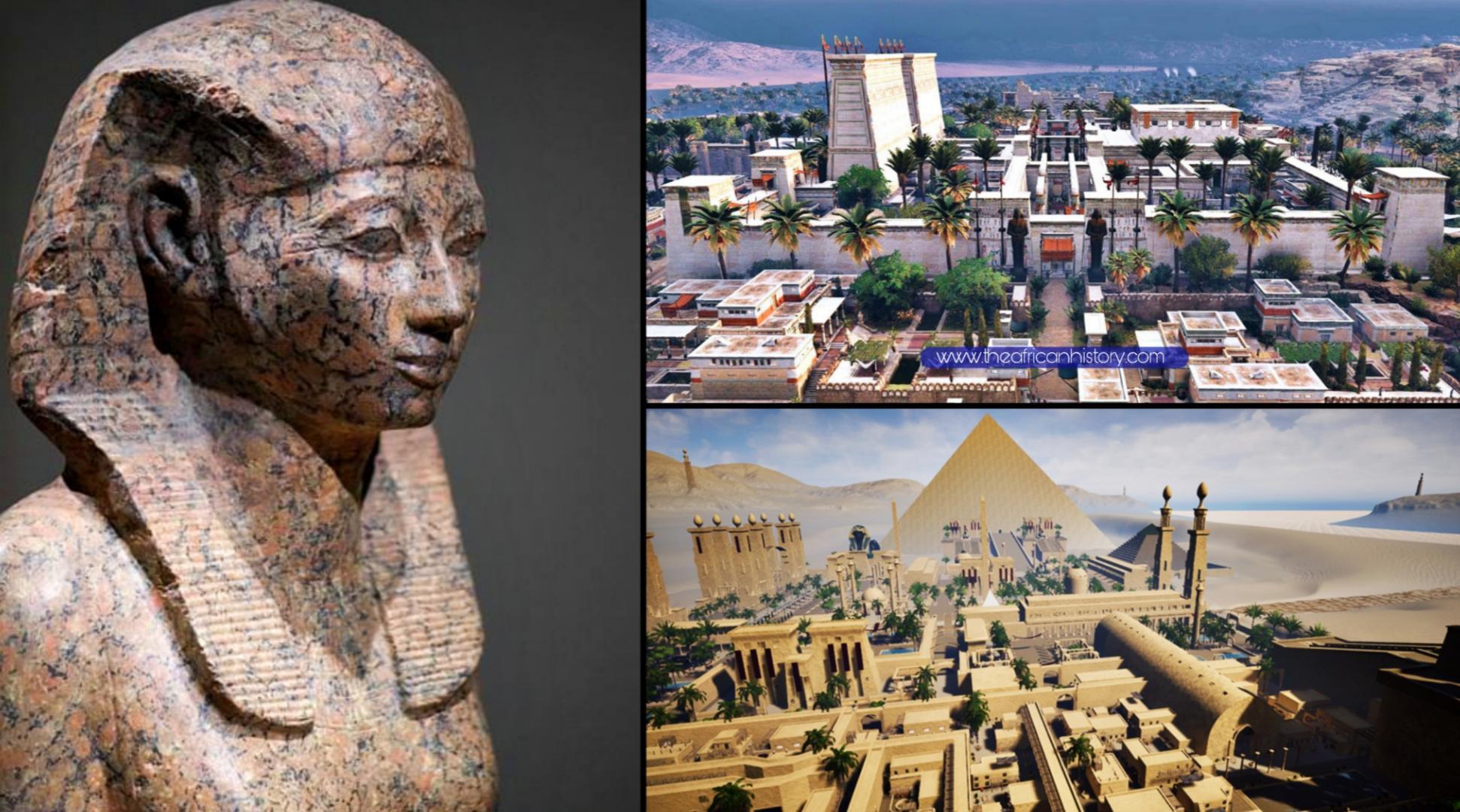

Hatshepsut was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, the first being Sobekneferu. Hatshepsut came to the throne of Egypt in 1478 BC.

Hatshepsut was only the second woman to become pharaoh in Egypt’s 3,000-year history, and the first to hold the entire power of the position. Cleopatra, who had similar power, reigned 14 centuries later.

Hatshepsut, the daughter of King Thutmose I, became queen of Egypt about the age of 12 when she married her half-brother, Thutmose II. She began acting as regent for her stepson, Thutmose III, after his death, but later assumed full pharaonic powers and became co-ruler of Egypt approximately 1478 B.C.

Hatshepsut, as pharaoh, expanded Egyptian trade and ordered large-scale construction projects, including the Temple of Deir el-Bahri in western Thebes, where she would be buried.

Hatshepsut was largely unknown to researchers until the 19th century, when she was shown (at her own request) as a male in several contemporary pictures and sculptures. She is one of Egypt’s few and well-known female pharaohs.

Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power

Thutmose I and his queen, Ahmes, had two daughters, the oldest of which was Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut became queen of Egypt when she married her half-brother Thutmose II, the son of her father and one of his secondary wives, who inherited his father’s kingdom around 1492 B.C. after her father died.

Neferure was their only child. Thutmose II died young, in 1479 B.C., and his newborn son, who was also born to a secondary marriage, inherited the throne. Hatshepsut began functioning as Thutmose III’s regent, administering governmental issues until her stepson reached the age of maturity.

Hatshepsut, on the other hand, took the unusual step of taking the title and complete powers of a pharaoh and became co-ruler of Egypt with Thutmose III after less than seven years.

Though previous Egyptologists believed Hatshepsut’s decision was motivated only by ambition, more current researchers believe it was motivated by a political problem, such as a threat from another branch of the royal family, and that Hatshepsut was acting to save the throne for her stepson.

Pharaoh Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut struggled to defend her power grab, citing her royal lineage and claiming that her father had designated her as his successor.

She wanted to change her image, so she requested that she be depicted as a male pharaoh with a beard and large muscles in statues and paintings of the time.

She did, however, pose in traditional female garb in other photographs. Hatshepsut surrounded herself with allies in high government positions, including Senenmut, her chief minister. Some have speculated that Senenmut was Hatshepsut’s lover, however there is little evidence to back this notion.

Hatshepsut, as pharaoh, embarked on a number of large-scale construction projects, primarily in the Thebes area. Her greatest work was the massive memorial temple at Deir el-Bahri, which is regarded one of ancient Egypt’s architectural wonders.

Another major accomplishment of her reign was the authorization of a commercial trip to Punt, which brought tremendous riches to Egypt, including ivory, ebony, gold, leopard skins, and incense, from a remote land known as Punt (possibly modern-day Eritrea).

Death and Legacy of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut would have been in her mid-40s when she died in 1458 B.C. She was buried in the Valley of the Kings, which is located in the hills behind Deir el-Bahri and also houses Tutankhhamum.

In yet another attempt to legitimize her rule, she had her father’s sarcophagus reburied in her tomb so that they may both die together. Thutmose III ruled for another 30 years, demonstrating that he was both an ambitious builder and a formidable warrior, like his stepmother.

Thutmose III had nearly all evidence of Hatshepsut’s authority erased late in his reign, including depictions of her as monarch on the temples and monuments she had erected, presumably to erase her example as a powerful female ruler or to close the gap in the dynasty’s male succession line.

As a result, Hatshepsut’s existence was unknown to ancient Egyptian researchers until 1822, when they were able to decode and interpret the hieroglyphics on the walls of Deir el-Bahri.

Hatshepsut’s sarcophagus (one of three that she had prepared) was discovered in 1903 by British archeologist Howard Carter, although it was empty, as were nearly all of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

A team of archaeologists uncovered her mummy in 2007 after initiating a new search in 2005. It is now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The Metropolitan Museum in New York City has a life-size statue of Hatshepsut seated that avoided her stepson’s destruction.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African