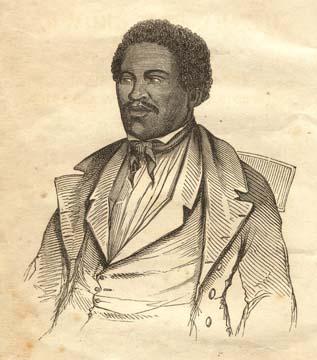

Henry “Box” Brown was born enslaved in Louisa County, Virginia in 1815. When he was 15, he was sent to Richmond to work in a tobacco factory.

His life was filled with unrewarding drudgery, though he had it better than most of his enslaved peers.

The loss of his freedom prevented him from living with his wife, Nancy, who was owned by a slave master on an adjacent plantation. She was pregnant with their fourth child when he received the devastating news in 1848: “Nancy and his children were to be sold to a plantation in North Carolina.”

He stood on the side of the street, tears in his eyes, watching 350 slaves in chains walk by, including his wife and their unborn child, as well as three young children. He could only wish them a tearful goodbye – he was helpless to save them.

Brown had also been paying his wife’s master not to sell his family, but the man betrayed Brown by selling Nancy and their three children while she was pregnant.

Escape

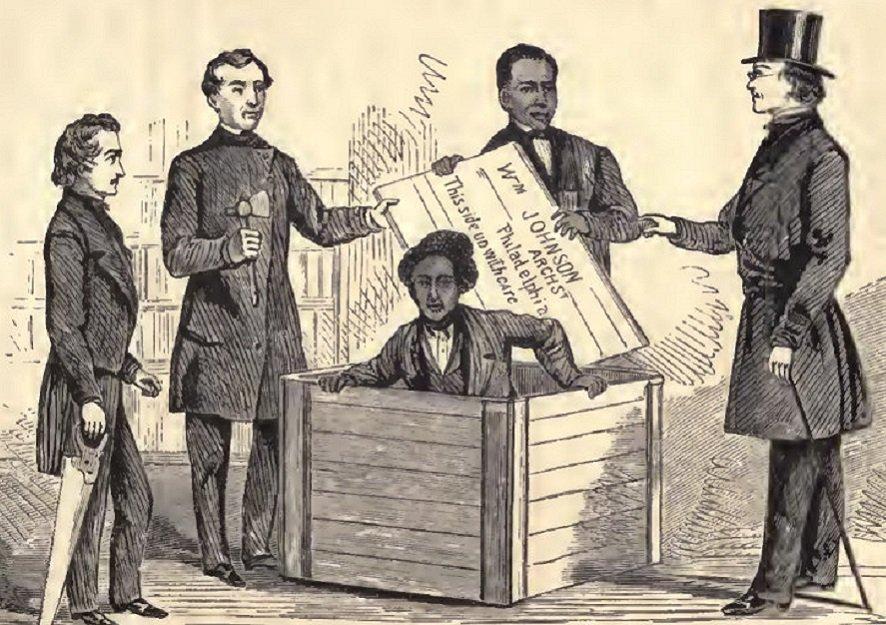

Brown devised a plan to have himself shipped in a box to a free state by the Adams Express Company, known for its confidentiality and efficiency, with the help of James C. A. Smith, a free black man, and a sympathetic white shoemaker (and likely gambler) named Samuel A. Smith (no relation).

Brown paid Samuel Smith US$86 (equivalent to $2,675 in 2020) from his savings of $166. Smith traveled to Philadelphia to consult with members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society on how to pull off the escape, where he met with ministers James Miller McKim, William Still, and Cyrus Burleigh.

After returning to Richmond, he corresponded with them to iron out the details. They advised him to mail the box to the office of Quaker merchant Passmore Williamson, a Vigilance Committee member.

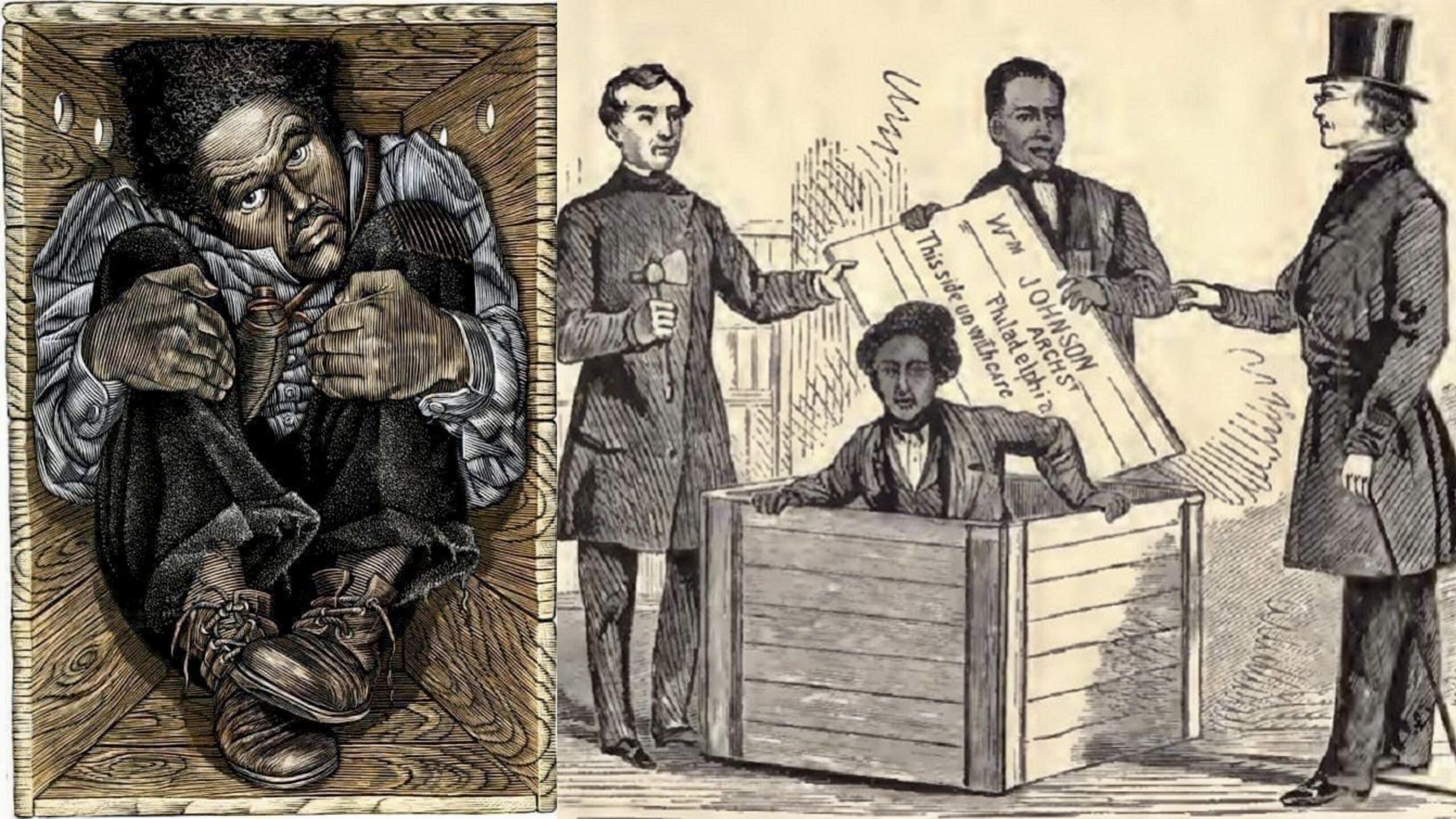

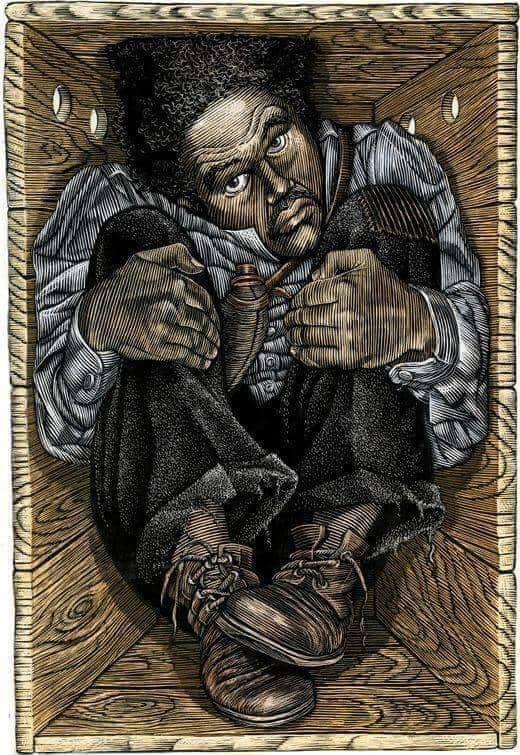

Brown burned his hand to the bone with sulfuric acid to get out of work on the day he was supposed to escape. Brown was shipped in a box that measured 3 by 2.67 by 2 feet (0.91 by 0.81 by 0.61 m) and was labeled “dry goods.” It was lined with baize, a coarse woolen cloth, and he only had a small amount of water and a few biscuits with him. There was a single hole cut for air, which was nailed and tied closed.

“If you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was, you cannot realize the power of that hope of freedom, which was to me indeed, an anchor to the soul both sure and steadfast,” Brown wrote later.

Brown’s box was transported by wagon, railroad, steamboat, wagon again, railroad, ferry, railroad, and finally delivery wagon during the 27-hour journey, which began on March 29, 1849.

Despite the “handle with care” and “this side up” instructions on the box, carriers frequently turned the box upside-down or handled it roughly. Brown remained completely immobile in order to avoid detection.

When Brown was finally released, one of the men remembered his first words to be “How do you do, gentlemen?” He sang a psalm from the Bible that he had chosen earlier to commemorate his freedom.

As Hollis Robbins points out, “the role of government and private express mail delivery is central to the story, and the contemporary record suggests that Brown’s audience celebrated his delivery as a modern postal miracle.”

Despite southern efforts to control abolitionist literature, mailed pamphlets, letters, and other materials reached the South thanks to the government postal service.

Brown’s escape demonstrated the power of the mail system, which connected the East Coast using a variety of modes of transportation. The Adams Express Company, a private mail service founded in 1840, advertised its secrecy and efficiency. It was popular among abolitionists because it “promised never to look inside the boxes it carried.”

Samuel Alexander Smith attempted to transport more enslaved from Richmond to freedom in Philadelphia, but was apprehended and imprisoned. James C. A. Smith was also arrested for attempting another slave shipment.

Brown rose to prominence as an abolitionist speaker in the northeastern United States for a brief period of time. Brown, as a public figure and fugitive slave, felt gravely threatened by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which increased pressure to apprehend escaped slaves.

He relocated to England and stayed for 25 years, touring with an anti-slavery panorama and working as a magician and showman. Brown married and had a family with Jane Floyd, an Englishwoman.

Samuel Alexander Smith attempted to transport more enslaved from Richmond to freedom in Philadelphia, but was apprehended and imprisoned. James C. A. Smith was also arrested for attempting another slave shipment.

Brown rose to prominence as an abolitionist speaker in the northeastern United States for a brief period of time. Brown, as a public figure and fugitive slave, felt gravely threatened by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which increased pressure to apprehend escaped slaves.

He relocated to England and stayed for 25 years, touring with an anti-slavery panorama and working as a magician and showman. Brown married and had a family with Jane Floyd, an Englishwoman.

Psalm

Song (modeled after Psalm 40), sung by Mr. Brown on being removed from the Box:

I waited patiently for the Lord

And he, in kindness to me, heard my calling

And he hath put a new song into my mouth

Even thanksgiving — even thanksgiving

Unto our God!Blessed-blessed is the man

That has set his hope, his hope in the Lord!

O Lord! my God! great, great is the wondrous work

Which thou hast done!If I should declare them — and speak of them

They would be more than I am able to express.

I have not kept back thy love, and kindness, and truth,

From the great congregation!Withdraw not thou thy mercies from me,

Let thy love, and kindness, and thy truth, always preserve me

Let all those that seek thee be joyful and glad!

Be joyful and glad!And let such as love thy salvation

Say always — say always

The Lord be praised!

The Lord be praised!

Henry “Box” Brown was widely recognized as a symbol of the Underground Railroad Freedom Movement. He was a man who combined bravery with creativity. Henry “Box” Brown quickly realized that he needed to reinvent himself in order to survive in the free world. He also realized that courage is not always bestowed upon you. “Continue to command me now as a freeman, to do the impossible!” he said in an act of faith to that “Higher Power” who gave him the creative idea to seek freedom in a box.

#BlackHistoryMonth #AfricanHistory #TheAfricanHistory

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African