The Zulu Kingdom, also called the Zulu Empire, was a Southern African state in what is now South Africa. During and after the Anglo-Zulu War, the small kingdom gained world renown, not least for initially defeating the British in 1879 at the Battle of Isandlwana.

This led in 1887 to the British annexation of Zululand, while the king’s office continued to be honoured (with the colonial title of Paramount Chief). However, even among the British, who appeared to look down on Africans as inferior, the Zulu gained a reputation for their bravery and ability as warriors.

“While the British discounted their defeat, in the anti-Apartheid struggle in white-dominated South Africa, where the Zulu nation became a “bantustan,” or homeland, the spirit and example of the Zulu warriors lived on to inspire many.

As part of a much larger Bantu expansion, the Zulus had initially trekked or migrated to Southern Africa and their Kingdom can be counted as one of several Bantu Empires, kingdoms and state systems that included Great Zimbabwe’s civilization.

The legacy of the Zulus is one of prestige in a highly organized African communities, which could resist the scramble for Africa, at least initially. When Africa was divided between European powers, they took over any territory they wanted without consulting Africans who own & occupied the land. Europeans enforced treaties backed up by military force.

They were soon defeated by those who refused to sign these treaties, such as the Sultan of Sokoto and the Obo of Benin. In the nineteenth century, Ethiopia alone resisted colonial occupation effectively, though in the twentieth century Fascist Italy exercised it briefly.

The Zulus are the largest ethnic group in South Africa, where they maintain pride in their heritage, history and culture despite the injustice of the Apartheid years.

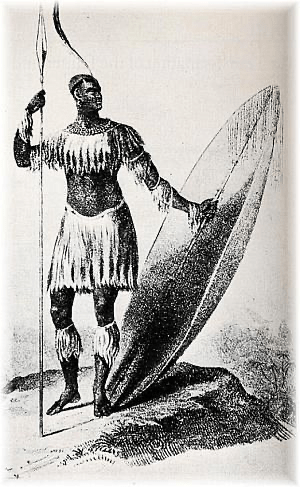

The rise of the Zulu kingdom under Shaka

Shaka Zulu was the legitimate son of the Ruler of the Zulus, Senzangakona. He was born in around 1787. He had been exiled by Senzangakona with his mother, Nandi, and found refuge with Mthethwa. Shaka fought under Dingiswayo, the chief of the Mtetwa Paramountcy, as a warrior. Dingiswayo helped Shaka establish his place as the Zulu Kingdom’s leader when Senzangakona died.

Dingane’s bloody ascension

Shaka was succeeded by his half-brother, Dingane, who collaborated with another half-brother, Mhlangana, to kill him. Dingane assassinated Mhlangana after this assassination and took over the throne. The execution of all his royal kin was one of his first royal acts. He also executed several past supporters of Shaka in the years that followed in order to protect his position. Mpande, another half-brother, was one exception to these purges, and was thought too frail to be a threat at the time.

Conflicts with the Voortrekkers and Mpande’s rise

The Voortrekker chairman Piet Retief visited Dingane at his Royal Kraal in October 1837 to discuss a land settlement for the Voortrekkers. In November, about 1,000 Voortrekker wagons descended the Drakensberg Mountains from the Orange Free State into what is now KwaZulu-Natal.

Retief and his members were requested by Dingane to return some cattle stolen from him by a local chief. Retief did so with his men, returning on February 3, 1838. A treaty was signed the next day in which Dingane ceded to the Voortrekkers all the land south of the Tugela River to the Mzimvubu River. Celebrations surfaced. Retief’s group were invited to a dance on February 6, at the end of the festivities, and ordered to leave their weapons behind. Dingane jumped to his feet at the height of the dance and shouted “Bambani abathakathi!” (isiZulu for “Seize the wizards”). Retief and his men were overpowered, taken to KwaMatiwane, a nearby hill, and hanged.

Some suggest that they were executed for hiding some of the cattle they had rescued, but it is likely that the agreement was a trap to destroy the Voortrekkers. A party of 500 Voortrekker men, women and children camped nearby were then attacked and massacred by Dingane’s army. Today, the site of the massacre is named Weenen, (Afrikaans “to weep”).

A new chief, Andries Pretorius, was elected by the remaining Voortrekkers and Dingane suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Blood River on December 16, 1838, when he [Dingane] talked a party of 470 Voortrekker colonists led by Pretorius.

Dingane burned his royal household after his defeat and fled north. Mpande, the half-brother spared from Dingane’s purges, defected with 17,000 supporters, and went to battle with Dingane along with Pretorius and the Voortrekkers. Dingane was assassinated near the modern Swaziland frontier. Mpande then seized control of the Zulu kingdom.

Succession of Cetshwayo

The Voortrekkers, under Pretorius, established the Boer Republic of Natalia, south of Thukela, and west of the British settlement of Port Natal (now Durban), in 1839 after the campaign against Dingane. Peaceful relations were preserved between Mpande and Pretorius. However, war broke out between the British and the Boers in 1842, resulting in Natalia’s British annexation. Mpande changed his loyalty to the British, and stayed with them in good terms.

In 1843, Mpande ordered a purge within his kingdom of suspected rebels. This resulted in several deaths, and the fleeing of thousands of refugees into neighboring areas (including the British-controlled Natal). Many of these refugees have left with their animals. Mpande proceeded to raid the surrounding areas, resulting in Swaziland’s invasion of 1852. The British, however, forced him into withdrawing, which he eventually did.

A war for succession broke out at this time between two of the sons of Mpande, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi. This ended with a battle in 1856 which left Mbuyazi dead. Cetshwayo then set about usurping the authority of his father. Mpande died of old age in 1872, and Cetshwayo took over power. There was then a border dispute in the Transvaal between the Boers and the Zulus, which now under British control, meant that they were now adjudicating between the two groups. The Zulu claim was favored by a commission, but a provision was added by the British governor requiring the Zulus to pay compensation to the Boers who would have to resettle.

Anglo-Zulu War

It was marked by a number of events, all of which gave the British an excuse to express moral indignation and anger about Zulu conduct. For instance, the estranged wife of a Zulu chief fled to British territory for safety, where she was killed. Regarding this as a violation of their own rule, the British sent an ultimatum to Cetshwayo on December 10, 1878, demanding that he disband his army. As he refused, at the end of December 1878, British forces crossed the Thukela river. The war was waged in 1879. Early in the war, at the Battle of Isandlwana on January 22, the Zulus defeated the British, but were badly defeated at Rorke’s Drift later that day. At the Battle of Ulundi on July 4, the war ended in a Zulu defeat. In order to subdue Africa and rule its colonies, Britain relied more on its military reputation, less on real power in the field, as McLynn comments:

The dominance of the colonial powers was founded on legitimacy, the belief that there was a military behemoth behind a small handful of officials, commissioners and missionaries that one called forth at one’s peril. This was why the British were forced to mobilize such force as was required to defeat Cetewayo by a serious military defeat, such as that inflicted by the Zulus at Isandhlwana in 1879, even though the empire did not hold any major interests in that part of Africa at that time.

However, even in defeat, the Zulu warriors gained the admiration of the British. During the long fight for citizenship and justice in white-dominated South Africa, the tale of early Zulu resistance to white colonialism was an inspiration to many Black South Africans.

The division and death of Cetshwayo

A month after his defeat, Cetshwayo was captured, then exiled to Cape Town. The British transferred the law of the Zulu kingdom to 13 “kinglets,” each with a sub-kingdom of their own. Between these sub-kingdoms, war soon erupted, and Cetshwayo was permitted to visit England in 1882. Before being allowed to return to Zululand, he had audiences with Queen Victoria and other famous characters, to be restored as king.

In 1883, Cetshwayo, much reduced from his original empire, was installed as king over a buffer reserve territory. However, Cetshwayo was targeted at Ulundi later that year by Zibhebhu, one of the 13 kinglets, backed by Boer mercenaries. Cetshwayo was wounded and fled. Cetshwayo, possibly poisoned, died peacefully in February 1884. His son, Dinuzulu, then 15, inherited the throne.

Dinuzulu’s Volunteers and final absorption into Cape Colony

In exchange for their aid, Dinuzulu recruited Boer mercenaries of his own, promising them land. These mercenaries called themselves “Volunteers of Dinuzulu,” and Louis Botha led them. In 1884, the Volunteers of Dinuzulu defeated Zibhebhu, and duly demanded their land. They were individually granted about half of Zululand as farms, and established an independent republic. This alarmed the British, who in 1887, then annexed Zululand. In later disputes with rivals, Dinuzulu became involved. Dinuzulu was charged in 1906 with being behind the Bambatha Rebellion. He was arrested for “high treason and public violence” by the British and put on trial. He was sentenced to ten years in prison on St Helena Island in 1909. Louis Botha became the first prime minister when the Union of South Africa was established and he arranged for his old ally, Dinuzulu, to live in exile on a farm in the Transvaal, where Dinuzulu died in 1913.

The son of Dinuzulu, Solomon kaDinuzulu, was never recognised as a Zulu king by the South African authorities, only as a local chief, but he was eventually regarded as a king by chiefs, political intellectuals like John Langalibalele Dube and ordinary Zulu citizens. In 1923, to promote his royal claims, Solomon established the Inkatha YaKwaZulu organisation, which became moribund and was then revived by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, chief minister of the KwaZulu Bantustan, in the 1970s. In December 1951, Cyprian Bhekuzulu kaSolomon, the son of Solomon, was officially recognised as the Zulu people’s Paramount Chief, but real control over ordinary Zulu people lay with white South African officials operating through local chiefs who could be removed from office for failure to cooperate.

In different parts of their empire, the British adopted the word “Paramount Chief” to appoint recognised traditional rulers in a way that left their own monarch as the only King or Queen. Therefore, “kings” have been demoted to “prince” or chief. Under Apartheid, KwaZulu’s homeland (or Bantustan) was established in 1950 and from 1970, all Bantu were considered KwaZulu citizens, not South African citizens, losing their passports. KwaZulu was abolished in 1994 and is now situated under the KwaZulu-Natal province.

During the anti-Apartheid struggle, pride in early Zulu resistance to the white domination and conquest of Africa helped inspire many people. Shaka was known as a national hero and the story of his life was re-enacted by many dramas. In 2004, thousands of Zulus took part in a re-enactment of Isandlwana’s victory to mark its 125th anniversary.

Kings of Zulu Kingdom

Mnguni

Nkosinkulu

Mdlani

Luzumana

Malandela kaLuzumana, son of Luzumana

Ntombela kaMalandela, son of Malandela.

Zulu kaNtombela, son of Ntombela, founder and chief of the Zulu clan from ca. 1709.

Gumede kaZulu, son of Zulu, chief of the Zulu clan.

Phunga kaGumede (d. 1727), son of Gumede, chief of the Zulu clan up to 1727.

Mageba kaGumede (d. 1745), son of Gumede and brother of Phunga, chief of the Zulu clan from 1727 to 1745.

Ndaba kaMageba (d. 1763), son of Mageba, chief of the Zulu clan from 1745 to 1763.

Jama kaNdaba (d. 1781), son of Ndaba, chief of the Zulu clan from 1763 to 1781.

Senzangakhona kaJama (ca. 1762-1816), son of Jama, chief of the Zulu clan from 1781 to 1816.

Shaka kaSenzangakhona (ca. 1787-1828), son of Senzangakona, king from 1816 to 1828.

Dingane kaSenzangakhona (ca. 1795-1840), son of Senzangakhona and half-brother of Shaka, king from 1828 to 1840.

Mpande kaSenzangakhona (1798-1872), son of Senzangakhona and half-brother of Shaka and Dingane, king from 1840 to 1872.

Cetshwayo kaMpande (1826 – February 1884), son of Mpande, king from 1872 to 1884.

Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo (1868-1913), son of Cetshwayo kaMpande, king from 1884 to 1913.

Solomon kaDinuzulu (1891-1933), son of Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, king from 1913 to 1933.

Cyprian Bhekuzulu kaSolomon (4 August 1924-17 September 1968), son of Solomon kaDinuzulu, king from 1948 to 1968.

Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu (b. 14 July 1948), son of Cyprian Bhekuzulu kaSolomon, king since 1971.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African