The New Kingdom, often known as the Egyptian Empire, was the time in ancient Egyptian history between the sixteenth and eleventh centuries BC, encompassing Egypt’s Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties. Radiocarbon dating dates the start of the New Kingdom between 1570 and 1544 BC.

The Second Intermediate Period was followed by the New Kingdom, which was followed by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt’s most prosperous period and the pinnacle of its power.

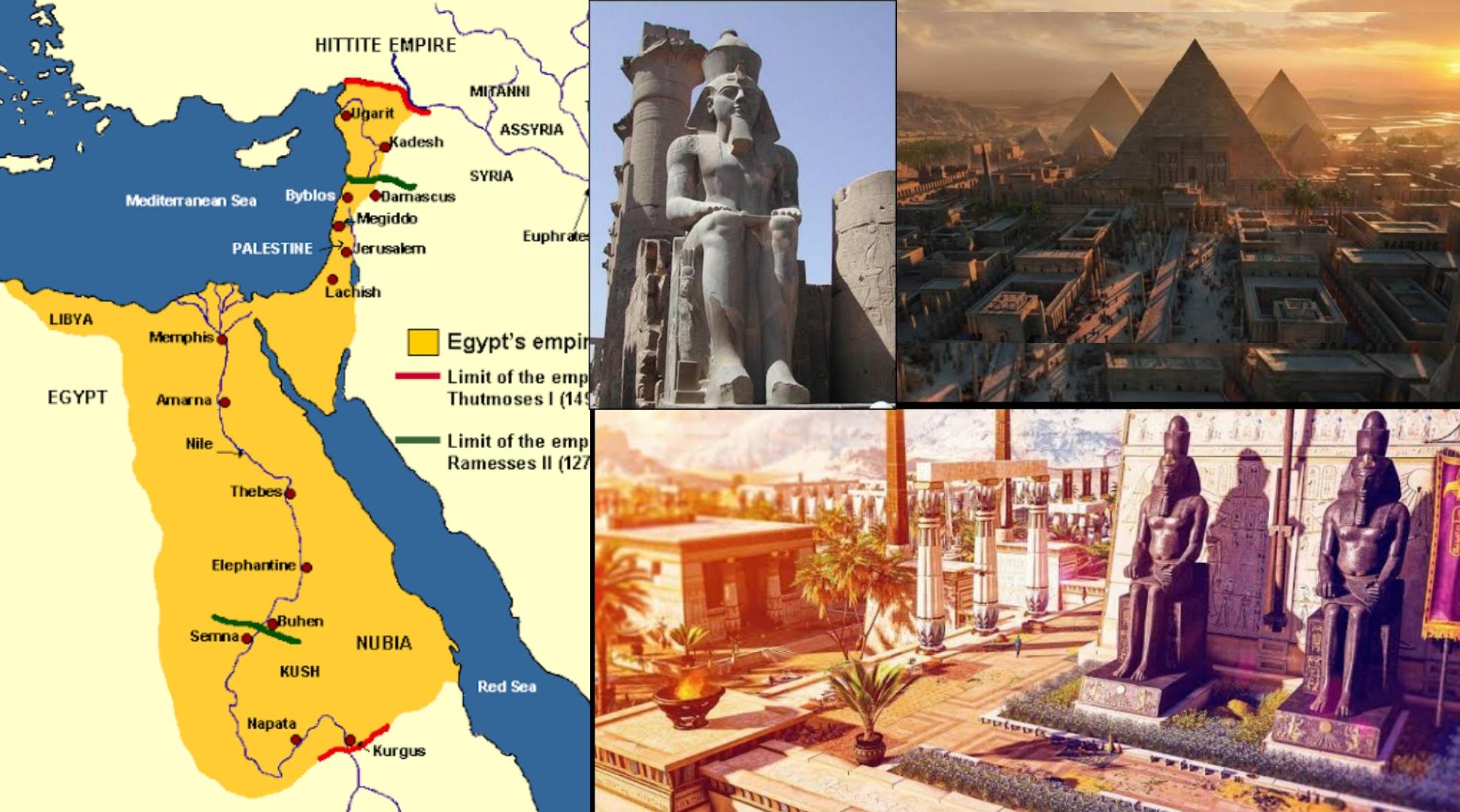

Egyptian Empire is believed to have started from c. 1550 BC to c. 1077 BC. New Kingdom at its maximum territorial extent in the 15th century BC. It first capital was Thebes before it was moved to Akhetaten, Pi-Ramesses and Memphis.

Common languages used were; Ancient Egyptian, Nubian and Canaanite. Religion was

Ancient Egyptian religion.

The first King (Pharaoh) of Egyptian Empire or The New Kingdom was Ahmose I who reigned from c. 1550 BC to c. 1525 BC. And the last Pharaoh was Ramesses XI, he reigned from c. 1107 BC to c. 1077 BC.

Rise of the New Kingdom (Egyptian Empire)

Some of Egypt’s most famous kings reigned during the Eighteenth Dynasty, including Ahmose I, Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun. Hatshepsut focused on developing Egypt’s external trade, including dispatching a commercial expedition to Punt, and prospered the country.

The eighteenth dynasty is thought to have been founded by Ahmose I. He maintained his father Seqenenre Tao’s and Kamose’s efforts against the Hyksos until he reunified the country. Ahmose would next continue his campaign in the Levant, the Hyksos’ home, to prevent future invasions of Egypt.

Following Ahmose was Amenhotep I, who campaigned in Nubia and was succeeded by Thutmose I. Thutmose I campaigned in the Levant, all the way to the Euphrates. As a result, he was the first pharaoh to cross the Nile.

The Syrian princes declared their loyalty to Thutmose throughout this expedition. When he returned, however, they stopped paying tribute and began fortification against future invasion.

Hatshepsut was one of this dynasty’s most powerful pharaohs. She was Thutmose I’s daughter and Thutmose II’s royal wife.

After her husband’s death, she governed jointly with his son by a minor wife, Thutmose III, who had risen to the throne as a child of roughly two years old, although she finally ruled in her own right as king.

Hatshepsut expanded the Karnak temple at Luxor and throughout Egypt, and she re-established trade networks that had been broken by the Hyksos rule of Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, resulting in the Eighteenth Dynasty’s affluence. She was in charge of the planning and finance for an expedition to the Land of Punt. Thutmose III ascended to power after Hatshepsut’s death, having earned vital experience as Hatshepsut’s military commander.

Thutmose III (“the Napoleon of Egypt”) enlarged Egypt’s army and used it successfully to consolidate the empire established by his forefathers. This culminated in a peak in Egypt’s strength and wealth during Amenhotep III’s reign.

During the reign of Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC), the term pharaoh, which was originally the name of the king’s palace, became a mode of address for the person who was king. Thutmose III, widely regarded as a military genius by historians, led at least 16 campaigns over the course of 20 years. He was an ardent expansionist emperor, dubbed “Egypt’s greatest conqueror” or “Napoleon of Egypt” by others.

During his reign, he is said to have seized 350 cities and conquered much of the Near East from the Euphrates to Nubia in seventeen recognized military campaigns. He was the first pharaoh to cross the Euphrates after Thutmose I, doing so during his war against Mitanni.

He marched north through the region of the still-unconquered cities of Aleppo and Carchemish, easily crossing the Euphrates on his boats and catching the Mitannian monarch off guard.

Amenhotep III, the wealthiest of this dynasty’s kings, built the Luxor Temple, the Precinct of Monthu at Karnak, and his huge Morturary Temple. Amenhotep III also constructed the Malkata palace, Egypt’s largest structure.

Amenhotep IV, one of the most well-known eighteenth-dynasty pharaohs, changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of the Aten, a personification of the Egyptian god Ra. His worship of the Aten as his personal deity is widely regarded as the first instance of monotheism in history.

Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s wife, made significant contributions to his new direction in Egyptian religion. Nefertiti was brave enough to execute Aten rituals. The religious zeal of Akhenaten is claimed as the reason he and his wife were eventually blotted out of Egyptian history. Egyptian art blossomed in a distinctive new form under his reign in the fourteenth century BC.

Egypt’s position had shifted dramatically by the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The Hittites had progressively extended their influence into Phoenicia and Canaan to become a major power in international politics, a power that both Seti I and his son Ramesses II would face throughout the eighteenth Dynasty, aided by Akhenaten’s apparent lack of interest in international affairs.

The last two members of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Ay and Horemheb, rose through the ranks of the royal court to become rulers, however Ay may possibly have been Akhenaten’s maternal uncle and a descendant of Yuya and Tjuyu.

Ay may have married the widowed Great Royal Wife and Tutankhamun’s young half-sister, Ankhesenamun, in order to gain power; she did not live long afterward. Ay then married Tey, who had previously been Nefertiti’s wet-nurse.

Ay’s rule was brief. His successor was Horemheb, a general during Tutankhamun’s reign who the pharaoh may have intended to be his heir if he had no surviving offspring, which he did. Horemheb may have seized the kingdom from Ay in a coup. Although Ay’s son or stepson Nakhtmin was named as his father or stepfather’s Crown Prince, Nakhtmin appears to have died during Ay’s reign, allowing Horemheb to take the throne next.

Horemheb died without surviving children as well, having named his vizier, Pa-ra-mes-su, as his heir. This vizier rose to the throne as Ramesses I in 1292 BC, becoming the first pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Height of the New Kingdom

The Nineteenth Dynasty was formed by Vizier Ramesses I, whom Pharaoh Horemheb, the last monarch of the Eighteenth Dynasty, had chosen as his successor. His brief reign was a transition time between Horemheb’s reign and the formidable pharaohs of this dynasty, particularly his son Seti I and grandson Ramesses II, who would push Egypt to unprecedented heights of imperial dominance.

During the first decade of his reign, Seti I waged a series of wars in Western Asia, Libya, and Nubia. The main source of information on Seti’s military activity is his battle scenes on the north external wall of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall, as well as other royal stelas with inscriptions referencing battles in Canaan and Nubia.

The conquering of the Syrian town of Kadesh and the adjoining area of Amurru from the Hittite Empire was Seti I’s greatest foreign policy triumph. Egypt had not possessed Kadesh since the reign of Akhenaten.

Tutankhamun and Horemheb had failed to retake the city from the Hittites. Seti I was successful in defeating a Hittite army that attempted to defend the town. However, after Seti’s departure, the Hittites reclaimed it.

Ramesses II (“the Great”) attempted to reclaim areas in the Levant lost to the 18th Dynasty. His reconquest expeditions culminated in the Battle of Kadesh, where he led Egyptian soldiers against the Hittite ruler Muwatalli II’s.

Ramesses was ensnared in history’s first known military ambush, but he was able to rally his forces and change the tide of battle against the Hittites thanks to the entrance of the Ne’arin (possibly mercenaries in the employ of Egypt).

The conflict resulted in a peace pact between the two nations, with both sides claiming victory on their home front. For more than a half-century, Egypt was able to achieve affluence and stability under Ramesses’ rule.

His immediate successors maintained the military campaigns, but an increasingly problematic court—which at one point installed a usurper (Amenmesse) on the throne—made it increasingly impossible for a pharaoh to properly keep control of the regions.

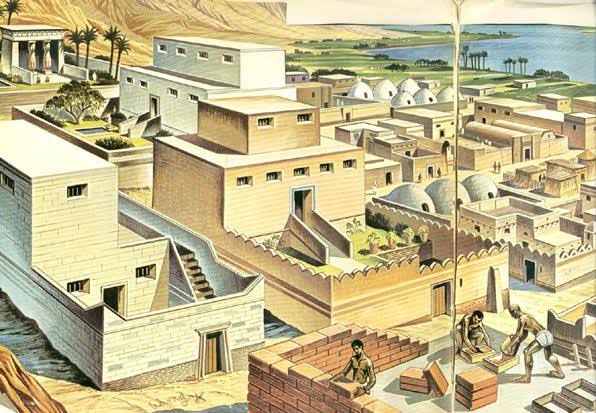

Ramesses II constructed extensively throughout Egypt and Nubia, and his cartouches are widely depicted even in buildings that he did not build. There are records of his glory carved on stone, statues, and the ruins of palaces and temples, most notably the Ramesseum in western Thebes and the rock temples of Abu Simbel. He filled the countryside with buildings from the Delta to Nubia in a way that no other king had before him.

During his reign, he also established a new capital city in the Delta called Pi-Ramesses. During Seti I’s reign, it was used as a summer palace.

Ramesses II built many huge monuments, including the archaeological complex of Abu Simbel and the Mortuary temple known as the Ramesseum. He developed on a grand scale to ensure that his legacy would outlast the ravages of time.

Ramesses employed art to promote his conquests over outsiders, which are shown on various temple reliefs. Ramesses II created more huge statues of himself than any other pharaoh, and he usurped many old statues by inscribing his own cartouche on them.

Ramesses II was also known for having a great number of offspring via his many wives and concubines; the tomb he erected for his sons (many of whom he outlived) in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be Egypt’s greatest funerary complex.

The military wars were maintained by Ramesses II’s immediate successors, despite an increasingly disturbed court. He was followed by his son Merneptah, and later by Merenptah’s son Seti II. Seti II’s legitimacy to the throne appears to have been challenged by his half-brother Amenmesse, who may have temporarily governed from Thebes.

Seti II’s son Siptah, who may have had poliomyelitis during his life, was elevated to the throne by Bay, a chancellor and a West Asian commoner who worked as vizier behind the scenes. Siptah died young, and the monarchy was taken over by Twosret, his father’s royal wife and maybe his uncle Amenmesse’s sister.

A period of instability at the end of Twosret’s brief reign saw a native reaction against foreign domination, culminating in the execution of Bay and the enthronement of Setnakhte, creating the Twentieth Dynasty.

Final years of power

Ramesses III, a Twentieth Dynasty pharaoh who reigned several decades after Ramesses II, is often regarded as the New Kingdom’s last “great” king.

The Sea Peoples invaded Egypt by land and sea in his eighth year as king.

Ramesses III defeated them in two major land and maritime engagements (the Battle of Djahy and the Battle of the Delta). He absorbed them as subordinate peoples and is assumed to have established them in Southern Canaan, however there is evidence that they forced their way into Canaan. Their presence in Canaan may have aided the creation of new nations, such as Philistia, in the region following the fall of the Egyptian Empire.

In his sixth and eleventh years, he was forced to combat invading Libyan tribesmen in two significant operations in Egypt’s Western Delta.

The high expense of this conflict gradually depleted Egypt’s treasury, contributing to the Egyptian Empire’s inevitable downfall.

The fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history happened during the twenty-ninth year of Ramesses III’s reign demonstrates the severity of the challenges. Food rations for Egypt’s preferred and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in Deir el Medina could not be provided at the time.

Air pollution reduced the amount of sunlight reaching the sky, reducing agricultural production and limiting global tree growth for about two decades, until 1140 BC. One potential explanation is the Hekla 3 eruption of Iceland’s Hekla volcano, however the timing of this remains uncertain.

Decline into the Third Intermediate Period

Ramesses III’s death was followed by years of wrangling among his heirs. Three of his sons succeeded him as Ramesses IV, Rameses VI, and Rameses VIII. Droughts, below-normal Nile flow, starvation, public upheaval, and official corruption plagued Egypt. The influence of the dynasty’s last pharaoh, Ramesses XI, waned to the point where the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became de facto rulers of Upper Egypt in the south, while Smendes governed Lower Egypt in the north, even before Ramesses XI’s death. Smendes eventually established the twenty-first dynasty at Tanis.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African