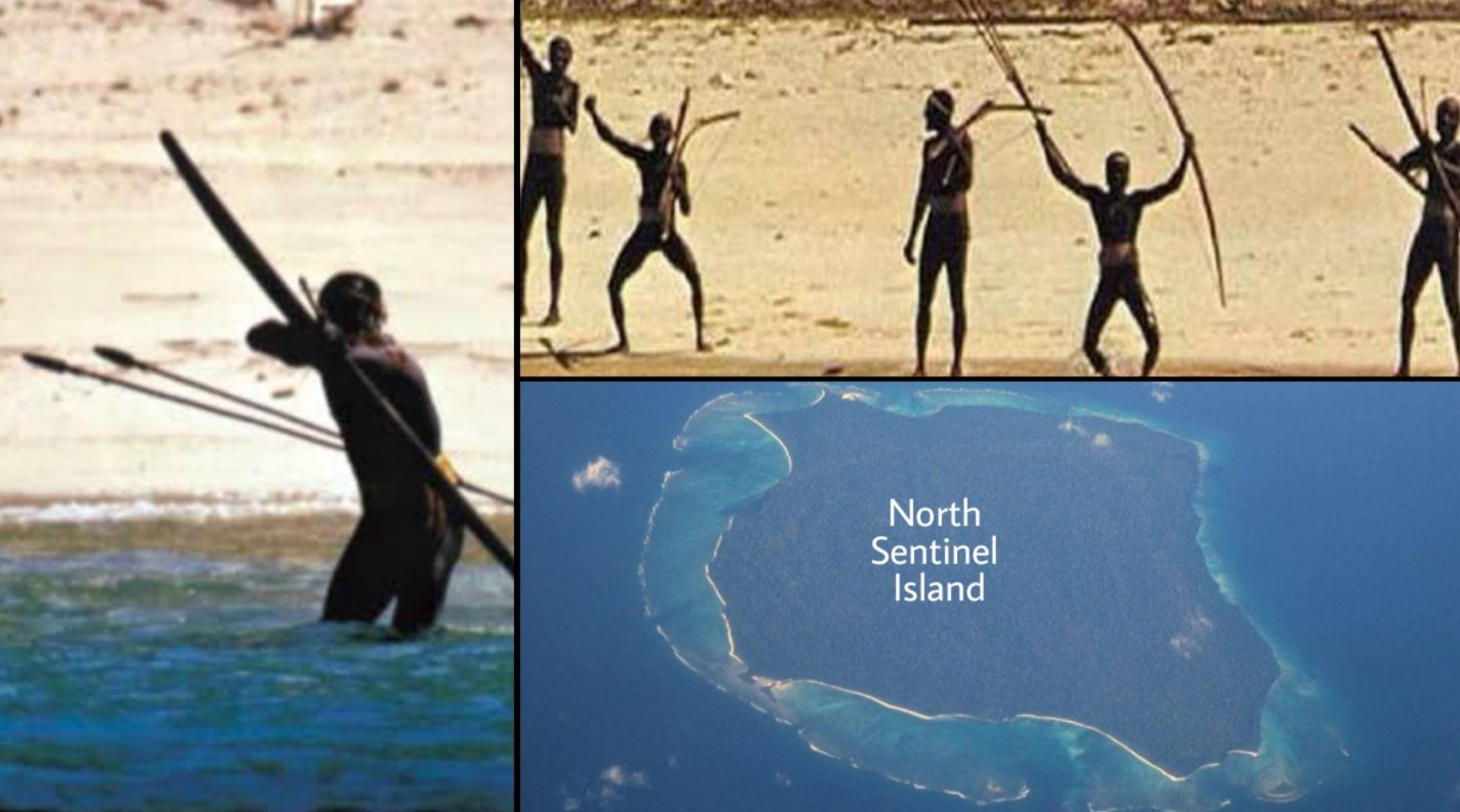

Sentinel Island, an archipelago in the Bay of Bengal which also includes South Sentinel Island, is one of the Andaman Islands. It is home to the Sentinelites, who have defended their safe isolation from the outside world, mostly by force.

The Sentinelese are commonly known as a tribe of the Stone Age, and historians believed they had been living in isolation for more than 60,000 years.

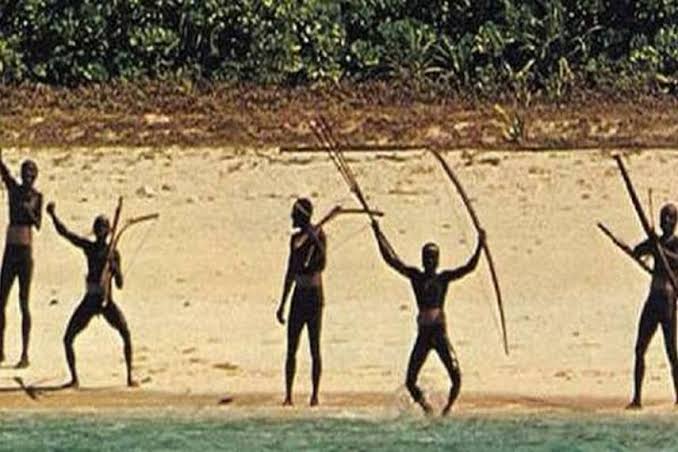

They hunt animals on a small, forested island with spears and arrows and arrows. They also collect green plants for food and to design into the homes.

Their closest neighbors are more than 50 kilometers away. They are highly suspicious of outsiders, threatening anyone who comes across the surf and their beaches.

In order to prevent resident tribespeople from contracting diseases to which they have no immunity, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Act of 1956 forbids travel to the island and any approach closer than five nautical miles (9.26 km). The Indian Navy patrols the area.

Traditionally, the island is part of the administrative district of South Andaman, part of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Indian Union Territory. In fact, Indian authorities recognize the desire of the people of the island to go alone and restrict their position to remote monitoring.

In 2018, the Government of India removed 29 islands – as well as the North Sentinel – from the Restricted Area Permit (RAP) structure until 31 December 2022 in a key attempt to boost tourism. However, in November 2018, the home ministry of the Government stated that relaxation of the prohibition was meant only to permit researchers and anthropologists, with pre-approved authorization, to visit Sentinel islands.

The Sentinelese have constantly attacked the approaching vessels. In 2006 two fishermen were killed and in 2018 John Allen Chau, a US missionary.

Geographical location

North Sentinel is located 36 kilometers (22 mi) west of the South Andaman Island town of Wandoor, 50 kilometers (31 mi) west of Port Blair and 59.6 kilometers (37.0 mi) north of its counterpart, South Sentinel Island. It has an area of about 59,67 km2 and of approximately 23,04 sq mi.

North Sentinel is surrounded by reefs of coral and lacks natural ports. Besides the shore, the entire island is forested. The island is surrounded by a narrow, white-sand beach, behind which the ground rises 20 m (66 ft), and then gradually to 46 m (150 ft): 257 and 122 m (400 ft) near the center. Around the island, reefs stretch from the shore to between 0.93 and 1.5 kilometers (0.5-0.8 nmi). At the edge of the reef, a forested islet, Constance Island, also called Constance Islet, is situated about 600 meters (2,000 ft) off the south-eastern coastline.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake tilted the tectonic plate underneath the island, lifting it 3 to 7 ft (1 to 2 meters). Significant parts of the adjacent coral reefs were exposed and became permanently dry lands or shallow lagoons, extending all the edges of the island on the west and south sides by up to 1 kilometer (3,300 ft) and uniting Constance Islet with the main island.

History

One of the other indigenous peoples of the Andamans, the Onge, were aware of the presence of North Sentinel Island; Chia daaKwokweyeh is their traditional name for the island. They also have clear cultural similarities with what little among the Sentinelese has been observed remotely. However, during the 19th century, Onges brought by the British to North Sentinel Island did not understand the Sentinelese language, so a lengthy split time is likely.

British visits

British surveyor John Ritchie noticed “a multitude of lights” from an East India Company hydrographic survey vessel, the Diligent, as it passed through the island in 1771. In March 1867, an administrator, Homfray, traveled to the island.

Nineveh, the Indian merchant ship, was wrecked on a reef near the island at the end of the summer monsoon season of the same year. The 106 surviving passengers and crewmen landed in the ship’s boat on the beach, fending off Sentinel attacks. Eventually, a Royal Navy search team located them.

Portman’s expeditions

In January 1880, an expedition led by Maurice Vidal Portman, a government administrator who hoped to explore the natives and their customs, landed on North Sentinel Island. The group had established a network of pathways and several small, abandoned villages. After a few days, six Sentinelese, an elderly couple and four children, were kidnapped and taken to Port Blair. The colonial officer in charge of the operation wrote that the entire group,

“sickened rapidly, and the old man and his wife died, so the four children were sent back to their home with quantities of presents”.

On 27 August 1883, after the eruption of Krakatoa and was mistaken for gunfire and understood as a ship’s distress signal, a second landing was made by Portman. A search party landed on the island and left gifts before returning to Port Blair. Between January 1885 and January 1887, Portman visited the island several more times.

On 27 August 1883, after the eruption of Krakatoa and was mistaken for gunfire and understood as a ship’s distress signal, a second landing was made by Portman. A search party landed on the island and left gifts before returning to Port Blair. Between January 1885 and January 1887, Portman visited the island several more times.

After Indian independence

Under instructions to create good relations with the Sentineles, Indian exploratory parties made brief landings on the island every few years beginning in 1967. In 1975, local dignitaries took Leopold III of Belgium on a tour of the Andamans for an overnight cruise to the waters off North Sentinel Island. In mid-1977, the container ship MV Rusley capsized on coastal reefs, and in August 1981, MV Primrose did so. It is understood that the Sentineles had scavenged both wrecks for iron. To retrieve the cargo, settlers from Port Blair also visited the sites. Salvage operators were allowed in 1991 to dismantle the vessels.

On 2 August 1981, after the Primrose had grounded on the North Sentinel Island reef, crewmen found several days later that some men carrying spears and arrows were constructing beach boats. Primrose’s captain radioed for an urgent drop in arms so that his crew could protect themselves. They did not obtain any because other ships were prevented from reaching them by a strong storm, but the rough seas also prevented the islanders from entering the ship. A week later, under contract with the Indian Oil And Natural Gas Corporation, the crewmen were rescued by helicopter (ONGC).

On 4 January 1991, Triloknath Pandit, the director of the Anthropological Survey of India, and his colleagues made their first friendly contact with the Sentinelese. While Pandit and his colleagues were able to make frequent friendly contact with the Sentinelese, dropping coconuts and other gifts, no progress was made in understanding the Sentinelese language, and if they stayed too long, the Sentinelese repeatedly warned them off. In 1997, Indian visits to the island ceased.

The Sentineles survived the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and its impact, including the island’s tsunami and uplift. Three days after the earthquake, a helicopter from the Indian government witnessed several islanders, who shot arrows and threw spears and stones at the helicopter. Although the tsunami disturbed the tribal fishing grounds, the Sentinelese appear to have adapted.

In January 2006 two Indian fishermen Sunder Raj and Pandit Tiwari surfed illegally in forbidden waters and were murdered by Sentineles when their boat was pushed too near to the Island. No prosecutions took place.

John Allen Chau, a 26-year-old US missionary trained and sent by All Nations based in Missouri, was murdered during an unauthorized trip to the restricted island in November 2018, intending to preach Christianity to the Sentinelese. On suspicion of helping Chau’s illegal entry to the island, seven people were taken into custody by the Indian police.

Under Indian law, entering a radius of 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) around the island is prohibited. Fishermen told police that they had seen the tribespeople drag Chau’s body around, but as of 25 November 2018, the authorities had not been able to verify his death independently. The case is being treated as a crime, but there was no indication that the tribesmen would be prosecuted.

Chau’s journal indicated that he was aware of the risks he faced, of having been shot by an islander with a bow and arrow on a previous attempt to visit, and of the illegality of his visits to the island. In a final note sent by the fishermen to his family, Chau wrote

“You guys might think I’m crazy in all this but I think it’s worthwhile to declare Jesus to these people. Please do not be angry at them or at God if I get killed …”

The family of Chau did not insist on the return of the body to the United States.

The Andaman and Nicobar (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956 provides protection for Sentinel and other native tribes in the region. The Andaman and Nicobar Administration stated in 2005 that they did not intend to interfere with the way of life or habitat of the Sentinel and that they did not wish to pursue any further contact with them or govern the island. Although North Sentinel Island is not legally an autonomous administrative division of India, scholars have referred to it and its people as effectively autonomous, or independent.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African