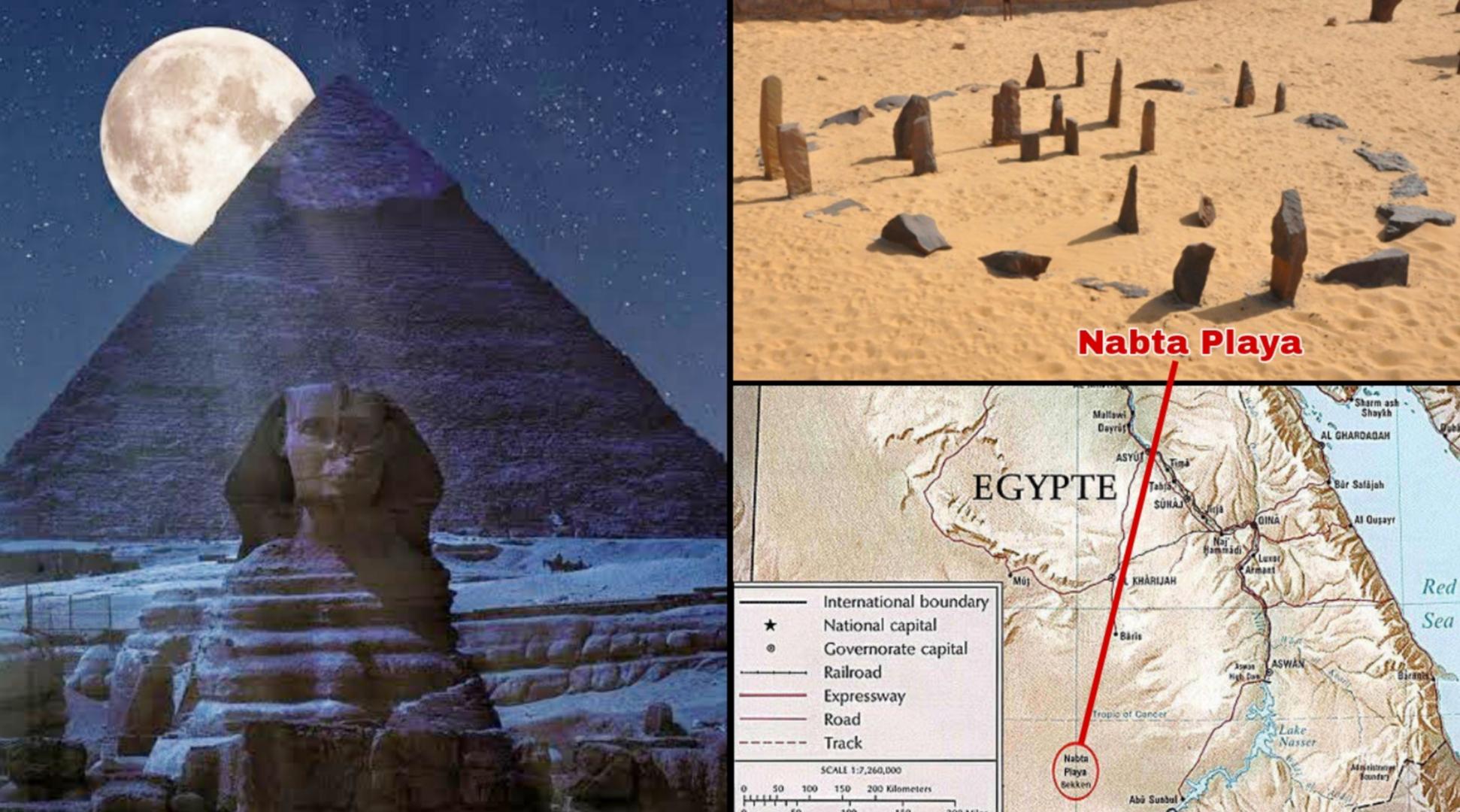

This 7,000-year-old stone circle tracked the summer solstice and the arrival of the annual monsoon season. It’s also the oldest known astronomical site on Earth.

For thousands of years, ancient civilizations around the world built huge stone circles to mark the seasons and align them with the Sun and stars.

These early calendars predicted the arrival of spring, summer, fall, and winter, allowing civilizations to prepare when to plant and harvest crops. They were also used as a sign of both joy and sacrifice.

These megaliths — massive, ancient stone monuments — can seem enigmatic in our modern era, when many people have no link to, or view of, the stars. Some also believe they are mystical or divined by aliens.

However, several ancient civilizations kept time by observing which constellations rose at sunset, similar to reading a massive celestial clock. Others also determined the position of the Sun in the sky on the summer and winter solstices, the longest and shortest days of the year, or the spring and fall lunar cycle.

There are approximately 35,000 megaliths in Europe alone, including several astronomically aligned stone circles, tombs (or cromlechs), and other standing stones.

The majority of these structures were constructed between 6,500 and 4,500 years ago, mostly along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

Stonehenge, a monument in England believed to be about 5,000 years old, is the most well-known of these sites. Stonehenge, though still ancient, may have been one of Europe’s youngest such stone structures at the time.

According to some historians, the regional practice of building megaliths first appeared along the coast of France due to the chronology and drastic similarity between these widespread European sites. It was then spread throughout the area, finally reaching the Great Britain.

However, even these primitive sites are centuries younger than the world’s oldest known stone circle, Nabta Playa.

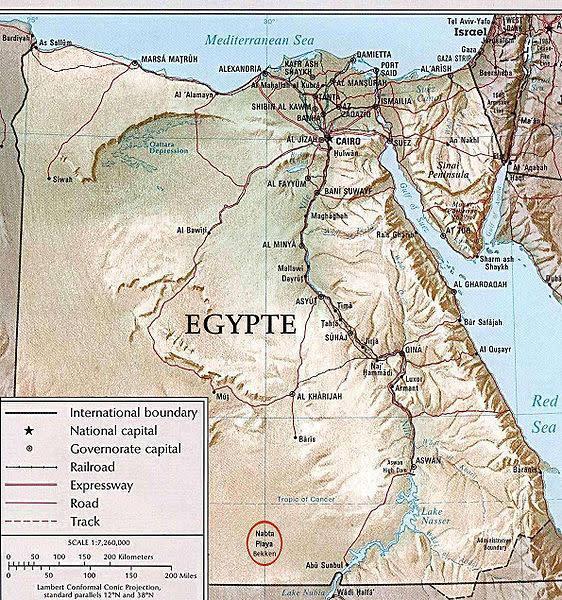

Nabta Playa is located in Africa, about 700 miles south of Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza. It was built over 7,000 years ago, making Nabta Playa the world’s oldest stone circle — and probably the world’s oldest astronomical observatory. It was built by a cattle-worshiping nomadic people to commemorate the summer solstice and the arrival of the monsoons.

“Here is human beings’ first attempt to make some serious connection with the heavens,” J. McKim Malville, a professor emeritus at the University of Colorado and archaeoastronomy expert, tells Astronomy.

“This was the dawn of observational astronomy,” he adds. “What in the world did they think about it? Did they imagine these stars were gods? And what kinds of connections did they have with the stars and the stones?”

The Discovery of Nabta Playa

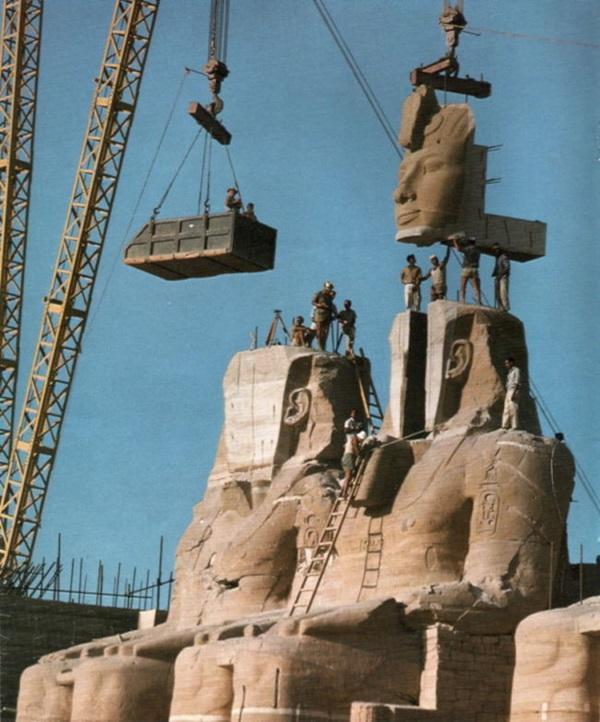

Egypt was preparing a massive dam project along the Nile River in the 1960s, which would flood significant ancient archaeological sites. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) stepped in with funds to assist in the relocation of famous structures as well as the search for new sites until they were lost forever.

But Fred Wendorf, a well-known American archaeologist, saw another possibility. He decided to go beyond the Nile River in search of the ancient sources of Pharaonic Egypt.

“While everybody else was looking at temples, [Wendorf] wanted to look at the desert,” Malville says. “He ushered in the predynastic period and the ancient kingdom.”

By chance, while crossing the Sahara in 1973, a Bedouin — or nomadic Arab — guide called Eide Mariff came across a group of what appeared to be massive stone megaliths. Mariff drove Wendorf, with whom he had collaborated since the 1960s, to the venue, which is about 60 miles from the Nile. Wendorf’s longtime friend and partner, Romuald Schild, recalls the discovery tale differently. He claims that in 1973, the entire team was traveling through this stretch of desert when they paused for a bathroom break. It was at this point that they discovered traces of megalithic remains.

Wendorf initially mistook them for natural formations. However, he soon realized that the location was once a huge lakebed, which would have ruined all such rocks. He would visit many times over the next several decades. Wendorf and a team of excavators, including Polish archaeologist Romuald Schild, then discovered a circle of stones that seemed to be aligned with the stars in some enigmatic way during excavations in the early 1990s.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African