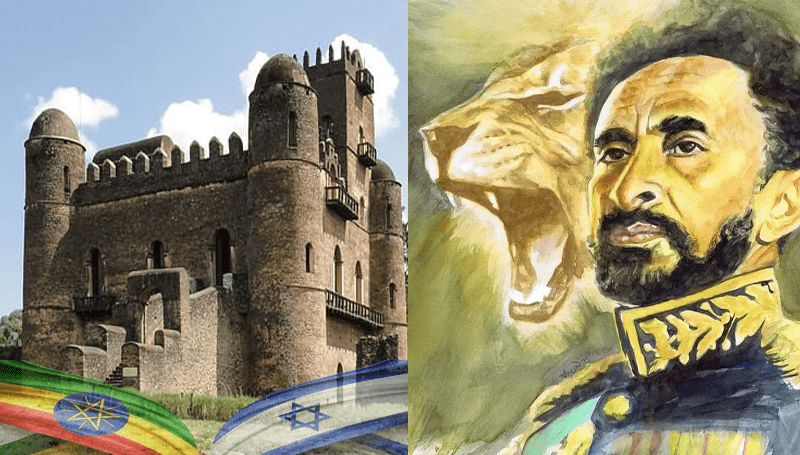

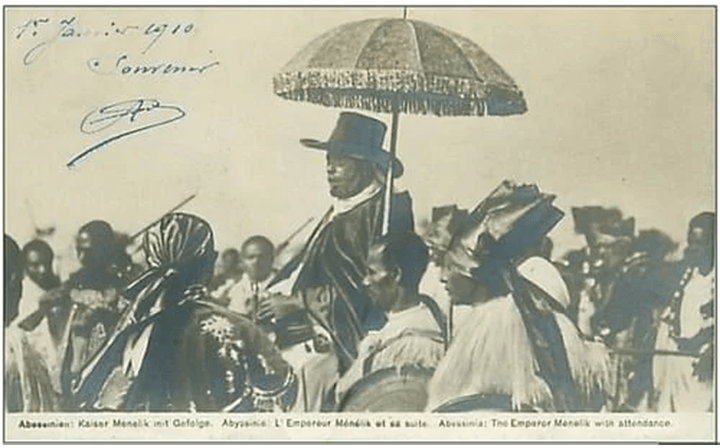

The Solomonic Dynasty, also called the Solomonic Restoration, was a time in Ethiopia’s history that ran from 1270 to 1636. It’s called that because when Emperor Yekuno Amlak became emperor in 1270, he said he was the direct descendant of Menelik I, son of King Solomon and Queen Sheba. This put an end to the short rule of the Zagwes, who didn’t claim to be Menelik I’s direct descendants.

During the Solomonic period, emperors did not use capital cities like rulers of earlier empires did. Instead, they had what were called “instant capitals” or “moving capitals.” The emperor, his army, nobles, and other members of the monarchy all lived in tents and huts.

They usually didn’t stay in one place for more than four months at a time. They moved when the land or the people there were no longer able to provide cattle, food, or anything else that was needed.

During the Solomonic period of Ethiopian history, the Christian highland and the Muslim coast were always fighting, often over trade routes. (Pankhurst 1998, 72) During the 14th century, Emperor Amda Seion and his son Sayfa Ar’ad, who took over after him, fought with the rulers of Ifat all the time.

Around the middle of the 16th century, Ahmad Gragn’s wars almost wiped out the Christian empire. Ahmad Gragn could only be defeated by the monarchy with the help of the Portuguese army. By the end of the 1600s, the Christian monarchy was much weaker than it had been at the start.

In the 1600s, Ethiopia was interested in becoming Catholic. After helping the monarchy beat Ahmad, the Portuguese stayed put and started spreading their religion. (Pankhurst 1998, 93-4) This was a problem for the emperors in the late 1600s and early 1700s, but when Susneyons took the throne in 1607, he was influenced by the Jesuits and thought it would lead to more military support from Portugal, so he slowly started to attack Orthodox Christianity and made Roman Catholicism the state religion.

Susneyons forced people to become Christians, but this only led to widespread rebellion, and the Portuguese didn’t send any troops to help. In 1632, the emperor gave in to what the people wanted and brought back Orthodox Christianity. (Pankhurst 1998, 103-7).

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African