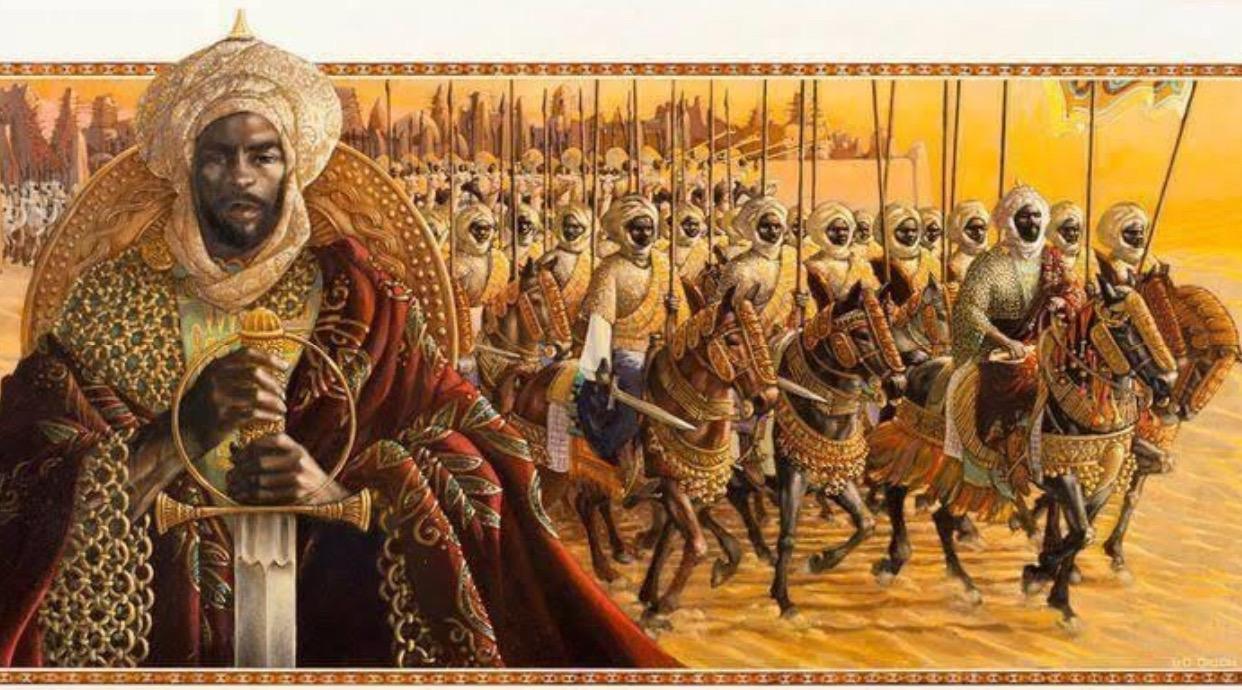

Sunni Ali established the West African Songhai Empire. He was best regarded as a great military leader, nicknamed Ali Ber, or “Ali the Great.” His views toward Islam are highly controversial.

Nearly little is known about Ali’s early life (who received the title of sunni, or si, when he became king of Gao) except that he grown up with the people of his mother, the Sokoto Faru, from whom he mastered the use of magical powers. As he grew older he lived with tenth si of Gao, his father, Madogo. Madogo was a good military leader, too, and he taught Ali magic skills. And by the time Ali became a si, he had become an expert in both fighting and magic arts.

When Ali succeeded the fourteenth si, Sulaiman Dama, in 1464, Gao was still a tributary province under the then declining Malian empire. Trade was becoming less stable in western Sudan as the Tuareg and the Mossi attacked more openly from the north and south.

As such, at a time when a power vacuum was emerging in the Niger Basin, Ali came to power in a centrally positioned and fairly powerful state and subsequently advanced against the Mossi, then proceeded to throw away the rule of Mali.

He succeeded in permanently freeing Gao from the once great empire of Mali, and laid the foundation for the much greater Songhai empire. Nevertheless, he could only defeat the Mossi in combat and never even tried to overcome those powerful non-Moslem rivals.

A majority of Ali’s political career has been spent subduing the Niger River’s great cities. He started a 7-year siege of the city of Djenné during the first year of his rule that, according to myths, had defeated 99 assaults by Mali. During the meantime he pushed further westward, crushing the Dogon and the Bandiagara Fulani.

He had added the Hombori to the south around 1467. The Tuareg had held Timbuktu since 1433, when it was taken from Mali. The local governor, Umar, petitioned Ali to come in 1467 to free his town from its invaders.

Ali advanced with such a overwhelming force in January 1468 that both the Tuareg and Umar themselves fled. The Songhay then stormed the town and sacked it. Ali ‘s brutal slaughter of most of the Muslim ulema there won him the absolute contempt and vituperation of the Muslim chroniclers who wrote the Tarikhs, comprising the principal written sources of his deeds.

Ali launched additional assaults on the Mossi, Fulani, Tuareg and other peoples in the subsequent years. The city of Djenné fell by 1471. Unlike the harsh treatment that Ali had done to the Timbuktu Muslims, who he felt had allied with a foreign enemy, he was benevolent here and accommodated the ulema.

Ali spread his conquests in all directions over the next decade but he continued to harbor a strong grudge against the Tuareg chief, Akil, who had fled after collapse of the Timbuktu. Akil had fled to Walata, and died there in 1480. Because much of Ali’s military power lay in his navy, the isolated plain town of Walata posed particular difficulties

Ali had conceived a bold scheme to build a canal between Lake Faguibine and Walata to send his navy in an assault. It was half the size of the new Suez Canal. But work was abandoned soon after the Songhai had to repel a nemesis attack, the Mossi.

Ali never resumed constructing this canal, but in Mali there are still signs of it.

Ali led more assaults on the Dogon (1484) and the Gurme, Tuareg, and Fulani (1488-1492) during the remaining years of his rule. In 1486 he again purged Muslims from Timbuktu.

The big issue for Sudanic emperors was that of balancing the interests of urban, or Muslim, against those of the much larger rural or non-Moslem population. Rulers were themselves usually Muslims, but they still had to remain tolerant of existing local religions.

Ali was a Muslim, following all of the daily Islamic rites; but he saw Islam as a possible obstacle to his political might. He wanted to maintain support among the rural masses, and he believed that if too many privileges were given to the urban Muslims he would be cut off from their support.

Ali’s contributions were mainly military. He was always on the move during the early years of his reign and he is known to have been undefeated. Nevertheless, the administrative restructuring role was left to its successor, Askia Muhammad.

Ali seems to have innovated a system of provincial governors, but it has not been implemented and Gao ‘s control over his new territories has been very strong. His military levies often upset Songhay agriculture, but he eventually alleviated this problem by incorporating more and more prisoners of war into his own forces.

Ali was more reliant on the fear and respect he commanded as a powerful magician-king than on the love and admiration of his subjects, for he was a cruel, short-tempered man. Occasionally he ordered only one trusted member of his retinue to be executed, only later to lament his error. His president, Askia Muhammad, avoided these hasty sentences many times.

Ali died in late 1492 upon his return from an expedition against the Gurma, probably drowned while crossing a river. His son Baru, who tried to reject all Islamic influence, succeeded him and was thus felled within 4 months by a Moslem-sanctioned coup led by Askia Muhammad.

The African History Truly African

The African History Truly African